Imagine for a second that you’re a kid again, and you’re fast. You’re really fast. You’re the fastest kid on your block. The fastest guy in your neighborhood. The fastest guy in your school. When you run, everyone else spends a lot of time looking at your backside as you pull away. You don’t run as much as you glide, effortlessly, as though you were born to do this one thing. In a way, you were. For you, running is effortless. You’re the fastest guy in every meet you enter. You’re the fastest kid in the county, the state.

You keep running. You start training with coaches whose whole purpose is to help you find ways to run faster. Your speciality is sprinting, a sport where every hundredth of a second matters. You train to shave .01s off your time. Every fraction of a tick is important. Imagine how many ticks in your life have gone by that you didn’t even notice, and now they all matter. You push every day to find ways to get faster. Your times keep getting better and better. You’re now the fastest guy at your university, the fastest guy at every meet, and those meets are full of runners who were the fastest guy on their street and at their school and in their state — until they ran against you. Imagine that for a second: You were faster than all of them.

One day, you go to a national meet, and you find out that you’re the fastest guy in your entire country. You go to bigger meets, and you win those, too. It’s hard to believe, but the results say it’s true: You’re the fastest guy on the entire continent. Imagine that: the fastest guy out of a billion people! You!

And imagine that you’re so fast that you make it here: To the Olympics. It’s 2008, and you’re in a stadium of tangled steel that the Chinese call the Bird’s Nest. You’re running faster than ever. You’re fast enough to make the quarterfinals of your best race, the 200 meter dash, and then the semis, and then the finals. There are almost 100,000 people in the stands to watch you run for a medal. Imagine: You are one of the eight fastest humans in the world, and now you will run to find out if you are the fastest.

You are not.

You are fourth fastest — still impossibly fast by any definition of the word, but no one seems to care, because the guy one lane over turns out to be the fastest man who ever lived. You are fast, but the guy in lane 5 is a tall Jamaican who runs at speeds that scientists said were unthinkable for humans to reach. He passes you less than five seconds into the turn — nearly impossible in the 200 meter! — and by the time you hit the straightaway, for once, you are looking at someone else’s backside. At the 150 meter mark, you could parallel park an SUV — not some rinky dink little thing, but a Cadillac Escalade — in the gap between him and you.

You still finish fourth in an Olympic final, the fourth fastest human in the world. You’re a quarter of a second away from a bronze, which is damn fast. You’re still the fastest guy on your continent, and an Olympian.

But the Jamaican in lane 5 finishes nearly a full second ahead of you. It’s impossible to imagine, but you try anyway: You are this fast, and yet, there is a human who is that much faster than you. The difference in that one second is the difference between you and sports immortality.

That one second is the difference between you and Usain Bolt.

———

I think about that 200 meter race a lot. I remember watching the finals live from my hotel room in Beijing, and I remember watching Usain Bolt pass the runner in lane 6 within steps. I couldn’t believe it then, and re-watching that race recently, I can’t believe it now. Bolt’s speed is unfathomable.

That runner I asked you to imagine? His name is Brian Dzingai, and he’s from Zimbabwe. He was the only African runner to make the 200 meter finals in Beijing. I like to think about the work he must have put in to make it to the Olympics. It must have taken an astonishing amount of work — physically, mentally, emotionally — to reach those starting blocks. I imagine that journey often, from the fastest kid on his street to one of the fastest men in the world. But I cannot imagine what it must have felt like to realize, after always being the fastest in every meet, to realize that there were humans who were actually faster than you.

I’ve written before about the idea of running your own race in life, and I’ll take the analogy a step further here: What I learned from watching that 200 meter race is that you truly cannot control what happens to the runners beside you. You cannot control how tall they are, or how fast they are. (Bolt was taller by a head, and faster by 0.92 seconds.) You cannot control the resources they have — money, training facilities, coaching. (Bolt surely had the better of all three.)

And you cannot control what you, yourself, are born with.

What you can control is this: The way you work. The hours you work. And the intensity with which you work.

Everyone else is going to run their race. You have to accept that you can only run yours.

When I re-watch that race, I always think about Brian Dzingai, and the work he put in to reach those starting blocks. There’s a man who imagined greatness in himself, and put in the work to be great. You can only control the work you do, and Brian Dzingai did just that. His work got him to the Olympics.

Here’s to you, Brian — and everyone else who puts in the work.

———

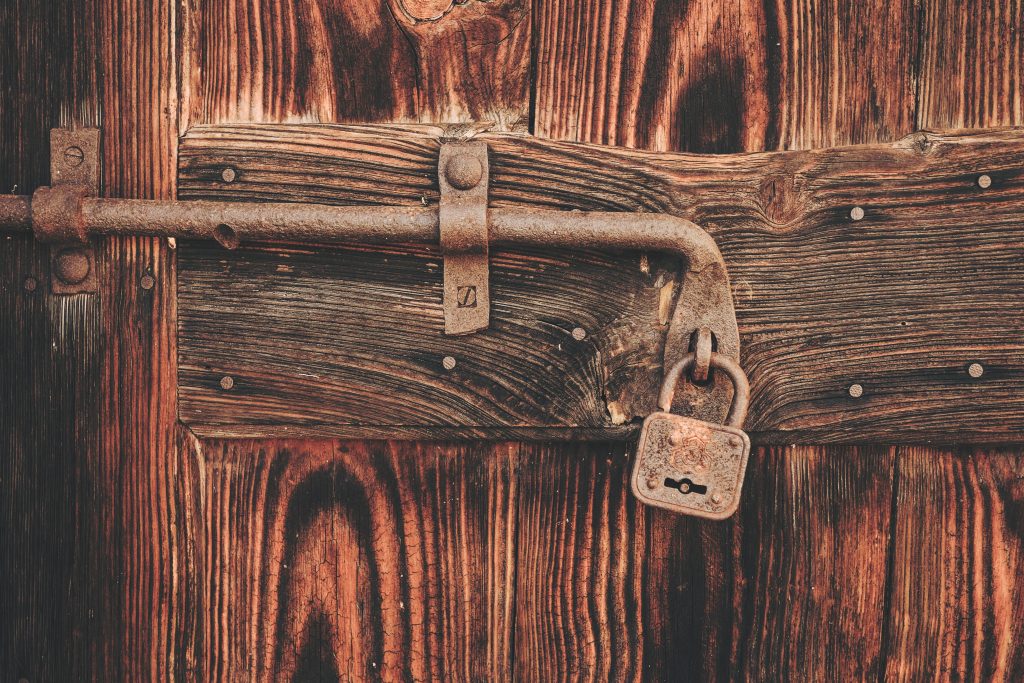

That photo was taken by photographer Ross Huggett at the 2012 London Games, and is used here thanks to a Creative Commons license and Flickr.