I am finding that lately, I have had to defend my choice of telephone. I find this strange, as my telephone does exactly what I want it to do: It places and receives phone calls anywhere in America.

The fact that it does this, and that I pay about $35 per month for such services, seems like a good deal to me.

And here’s what I really like. My telephone does more than just handle phone calls. It can also send and receive text messages, which are growing on me as a legitimate tool for communication. It features voicemail, which is quite a bit more affordable than hiring a secretary to handle similar message-taking duties, and it has a few spiffy additional features, such as a tip calculator and alarm clock. The calendar function is especially useful, and can be used for such purposes as finding out what day it is.

Again, I thought this was a lot for a cell phone to offer.

The good folks at CNET had this to say about my phone:

“In any case, the SGH-A137 isn’t too much to get excited about. The simple flip phone is so basic that it doesn’t even offer an external display.”

Oh.

What I am discovering is that my colleagues agree with the editors at CNET. They tell me that more than my clothes, or my choice of automobile, or my chosen profession, my phone indicates what kind of human I am.

I thought my phone indicated that I was both sensible and uncomplicated.

Not even close.

Not even in a million, billion years. Just NO, Dan.

What my phone apparently signals to others is that I am, at best, uncool, and at worst, a lost cause. There is only one remedy for someone like me:

A smartphone.

A smartphone like the iPhone, or the Blackberry, or something that runs on Android. A phone capable of listening to a song on the radio, determining what song I’m listening to and then automatically downloading said song to the phone’s very hard drive. A phone capable of taking a photo and then rendering it in sepia. A phone capable of booking reservations at a nearby restaurant, testing my food for any toxins, chewing my food, paying my bill, getting me a taxi home, tucking me into bed and telling me a bedtime story.

A phone like that, or something.

I do not like that sound of that. Not at all.

See, I have a very simple mind. I actually like dividing up my devices into specific silos. I like reading on my Kindle. I like typing on my laptop. I like rocking out on my iPod. I like calling on my phone. This system works nicely for me.

And I suppose that, yes, I could get a singular device that could allow me to do all of those things. But I type slowly on a phone. I don’t like reading something on a three-inch screen. I like going for a jog and not having my music device start vibrating from an incoming text.

More than anything, I love disappearing. When I am at my computer, I respond to email. I write. I’m busy.

But away from that screen? I shut down. Work ends. I go out, and I enjoy life in this rather nice world of ours. If you need me, call me. I’ll pick up. But that email of yours will have to wait.

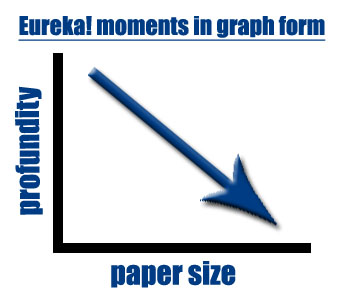

Give me a smartphone and I’d be in a state of perpetual Google. I’d be walking down the street and see a Curly W hat and ask myself, Who was it who hit 3rd for the Nationals in 2006?, and then I’d lose myself in the lifetime statistics of Jose Vidro, and then I’d pour over numbers on Baseball Reference, and then I’d find myself wondering what just happened to the previous 35 minutes. I know, because this is what happens at work. I take a thought, and connect it to another, and another, and then the time just disappears. I am good at wasting time, and on a smartphone, I would waste an awful lot of it.

My current phone? I don’t get lost in it. I make my call. I send my text. I move on. I leave myself time to stop and stare.

It is a phone that allows me to focus completely on what I am doing.

Of course, now that I’ve said all that: I’m going to get lost on the way downtown tonight. I’m going to need directions. A song will come on the radio, and I’ll want to download it. I’ll forget to make reservations at the place I’m headed. I’ll see something that demands to be sepia-ized. I’ll have an urgent email to send out.

And I’ll understand why everyone else has that thing in their pocket.

But me? No. Not yet. Not ever, I hope.