Things tend to go wrong. This is a series of blog posts about the things I think about during those moments when the wrong things happen.

I went to the Super Bowl once. It was fourth grade, and Dad got tickets. The Chargers played the 49ers in Miami. The halftime show was a combination of Indiana Jones and the Miami Sound Machine. There was a 99-yard kickoff return by the Chargers, and Jerry Rice scored the first touchdown for the Niners, and Natrone Means didn’t have a very good game, and I don’t remember anything else. The 49ers won big, and we got to take our official Super Bowl XXIX seat cushions home. That’s what I remember about the game.

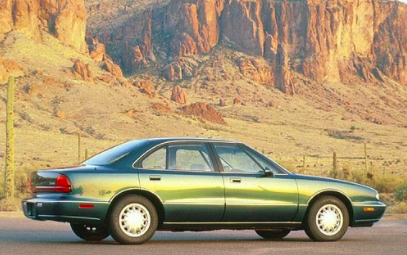

But I also remember that we left the game early. Dad never leaves games early — never. We stay the full nine; we play the full 60 minutes. Always. That night was an aberration. We were driving my grandpa’s car, and we didn’t really know our way around Miami, so Dad wanted to leave before the crowds starting filing out.

On the way in, we’d found ourselves an easy target to help us find our car: A 20-foot tall inflatable Lombardi Trophy. We parked right next to it, and we figured that it wouldn’t be too hard to find the giant silver football on the way out.

Except that they’d moved the trophy.

During the pregame show, we’d actually seen it, down on the field. They’d brought it inside the stadium for the fireworks and the flyover and the anthem and all that. Dad had pointed it out; we just didn’t know that the NFL only had one giant inflatable Lombardi Trophy at the Super Bowl that night.

So we walk out of the stadium, and the parking lot is almost completely unlit. The only light’s the one coming out of the stadium, and the light and noise is flooding out of there. But out in the parking lot, it’s dark. And we’re looking around, and we can’t find our giant Lombardi Trophy, and we’re realizing that it’s long since been deflated and is somewhere underneath Joe Robbie Stadium.

Joe Robbie seats 75,000 fans, and there are 60,000 cars out in the parking lot, and we’re looking for a late 80s Mercedes station wagon, and we can’t see anything, because it’s pitch black, and any minute, 75,000 fans are going to walk out of Joe Robbie, and we’re going to be stuck in the parking lot forever.

This was fourth grade, when the keyless entry — or as my mother still calls it, the Boop-Boop — was just becoming a thing. Grandpa’s car didn’t have it. So we couldn’t even just walk around pressing the button on the keys, hoping the car might honk back at us. We were really, really lost.

I remember dad saying that maybe our best option was just to wait for all the cars to empty out of the parking lot. Once all the rest of the cars were gone, it probably wouldn’t be that hard to find ours — theoretically speaking.

Dad wasn’t all that enthused about the prospect of us spending the night wandering around a Miami parking lot, just a a dad and a 10-year-old, two seat cushions, one wallet and a whole lot of dark.

We kept walking around.

I don’t remember when we found the car, only that we did. I don’t remember how long we walked around the parking lot — 15 or 20 minutes, at the least. It seemed longer. When you’re unhappy and lost, time always seems to stretch.

Now for a happier thought: High up on the list of things that comfort me when everything goes wrong, there’s Explosions in the Sky. They’re this amazing instrumental band from Austin, and they have this way of turning little moments in life into something worthy of Technicolor. I love one of their songs most of all: “Your Hand in Mine.” There’s a moment in the song, about two minutes in, where the song just breaks, and out of it comes this simple, soaring set of chords. No matter how fucked I am, no matter how bad things seem, that little melody reminds me of how things will pass. I listen to them, and good things always seem to come this way.