Things tend to go wrong. This is a series of blog posts about the things I think about during those moments when the wrong things happen.

I had Mrs. Buckingham for 10th grade English. I don’t remember that much about her anymore; I do seem to recall that she had white hair, and she was slightly plump, but I’m not quite sure about anything beyond that; in my mind, I’ve kind of replaced her with Mrs. Doubtfire.

But I do remember that in the spring semester, she assigned each student something grammar-related and asked us to give a presentation about it. Some students were assigned punctuation marks, or something relating to syntax.

I was assigned the anecdote.

And then I did what 10th graders do on semi-meaningless presentations: I stalled. For a month, I did nothing. I watched other students give five-minute mini-lectures on the exclamation point and the semi-colon. But I knew I didn’t have to present for a few weeks.

So I did nothing.

A week passed. Then two. Then three. The weekend before my presentation — I remember I was presenting on a Monday — I decided I had to start on my big anecdote presentation.

Except that I didn’t. I watched some football on Saturday. Went out with some friends that night. And then it was Sunday — the last day. I was all set to figure out how to explain the mystery that is the anecdote to my peers.

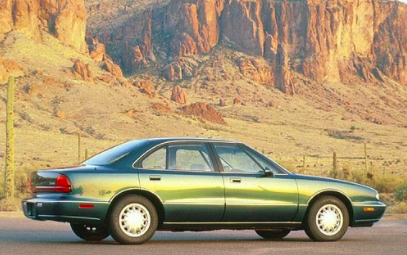

And then my friend, Sam, called, and asked if I wanted to go play golf with our friend, Brett. I did. I had a red Oldsmobile 88 that had been handed down from my grandpa. It had these cloth seats that you just sunk into, and the front seat was actually a bench seat, so the thing seated three in both the front and the back. The 88 was as wide as a Suburban and nearly as long; parallel parking it felt a little like parking a small cruise ship. The 88 had a trunk that sunk down almost to the pavement, and it was plenty big enough for three sets of golf clubs. So we took my car.

I don’t remember much about the round we played. What I do remember is the drive back down I-270. I was in the left lane, and the 88 had a way of lulling me to sleep in those big, cloth seats. I looked up at the dash at one point and realized that I was doing 90+ in a 55. The 88 was deceptively fast like that, but it also wasn’t much designed for high speeds. I’m not sure Grandpa ever put the thing above 35 in all the years he drove it.

So the car started to rattle a little bit, but nothing too frightening. We pulled off the highway to drop off Sam. Sam lived down Seven Locks, a windy, up-and-down-and-up-again of a street, and when we got to Sam’s house, I remember going over this bump, and then I remember hearing a noise that sounded distinctly like a 777 flying by at low altitude.

I thought nothing of it, but when Sam was walking with his clubs into his garage, he looked back and noticed that part of the underside of my car was falling off.

Turns out that somewhere between the high speeds and the bumpity-bump of Seven Locks, the splash guard for my engine — basically, this piece of plastic that kept water from getting into parts of the engine that weren’t supposed to get wet — had lost a screw or two, and had started dragging on the ground.

But the three of us didn’t know this. We weren’t car experts. We were 16. My car knowledge was limited to whatever I’d heard on “Car Talk.” I was unaware that the splash guard is kind of like the human appendix; it has a purpose, but not much of one.

I saw this thing dangling underneath my car and assumed that it was the part of the engine that kept the rest of the engine from, you know, just falling out onto the street. I saw this part and assumed that it was, in the most meaningful sense of the word, essential to the working ability of my motor vehicle.

So we did what any 16-year-olds would do in a situation where our mode of transportation was on the verge of collapse: We went into Sam’s garage, grabbed a roll of duct tape and turned the underside and front of my car into a rolling 3M ad.

And then I drove off for Brett’s house at about 25 miles an hour.

Somewhere along the way, I started to fear that my 88 was basically turning into the sled from “Cool Runnings,” and that my carburetor or something equally important-sounding was just going to plop out and land on River Road, and my parents were going to kill me.

And then I realized that I was going to have to explain this whole thing — the whole, Uh, I think my engine is dangling by a thread and some duct tape situation — to my mother.

But then, while slowing down traffic and doing 25 in a 45, I realized what I had to do: When I saw my mother, I had to lighten the mood. I had to walk into the house and tell her something that would distract her from the disaster that was my car. I had to tell her something that would simultaneously make her laugh and help her understand the situation.

What I needed was an anecdote. Only an anecdote would do.

And suddenly, I knew just what I’d be talking about in Mrs. Buckingham’s class the next day.

Which brings me back to this:

When I’m convinced that every fucking thing is going wrong, what I find is that it usually helps to think about how absurdly tiny my problems are. This fantastic little narrative by Carl Sagan is especially helpful. It is the very definition of perspective.

In it, he points to a photo of Earth as taken from millions of miles away. The earth is just a tiny blue dot in the photo. And Sagan says:

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every ‘superstar,’ every ‘supreme leader,’ every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there–on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

“The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

“Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light.”

And holy mother of Buddha does that make every mistake seem a little less epic.