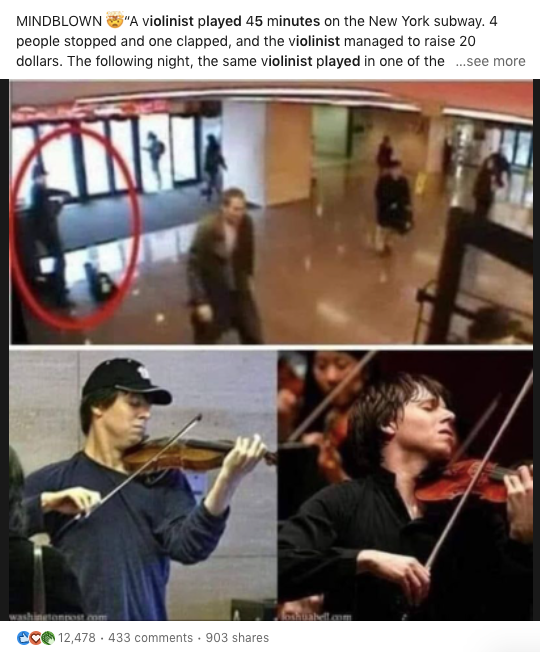

I was scrolling through LinkedIn last weekend, and in a span of two minutes, saw the same story — same copy, same three images — pop into my feed twice.

The story was about Joshua Bell, one of the most acclaimed violinists of our era. He’ll soon be playing live with orchestras in Portland, Oregon, Stockholm, Sweden, Yerevan, Armenia, and Paris, France — and that’s just in the next four weeks. He performs on a Gibson ex Huberman, crafted by Antonio Stradivari in 1713, a violin twice-stolen and most recently purchased for a reported $3.5 million. And in January 2007, as part of an experiment with The Washington Post, during the morning rush hour at Washington’s L’Enfant Plaza, he performed six classical pieces over the course of 43 minutes, as workers hurried from the Metro station to their offices. The experiment, as the Post’s Gene Weingarten explained, was to answer a simple question: “In a banal setting at an inconvenient time, would beauty transcend?”

Now, you might already know the answer to that question — possibly because you remember the story, which won a Pulitzer Prize, or possibly because you’re smart enough to guess the answer (“no”), but most likely because you’ve seen a version of this story pop into one of your social media feeds over the past 15 years, just as I did over the weekend.

And that version of that story was almost certainly wrong.

Weingarten, the writer of the original piece, tried to set the record straight in a 2014 column. After the piece was published, someone published a summary of the piece to the web. Weingarten found sixteen different errors in it — impressive when you consider that the summary was only 24 sentences long. As he explained:

“This piece — most people’s only direct knowledge of the stunt and its aftermath — was filled with errors significant and trivial, but relentless in their carelessness. I just re-read it, and it is almost incomprehensible how this could have happened, unless the writer read the original piece, forgot about it, and then, months later, tried to summarize it from memory, as though it were not available in original, checkable form just a few clicks away.”

That summary has since been copied and pasted thousands upon thousands of times, and has slowly gathered additional errors as it moves around the web. In the error-filled 2014 version, six people stopped to listen to Bell’s performance, and in total, he made $32. In the 2022 LinkedIn version, of which there are hundreds of posts with identical copy and identical images, four passerbys stopped, Bell made $20, and also, the entire thing took place in New York. (For the record: It took place in Washington, seven stopped, and he made a little more than $32, not including a larger bill dropped in by the one Washingtonian that day who happened to recognize him.)

People share this story for all sorts of reasons. I remember reading it in 2007 as a Ferris Bueller-esque reminder to stop and look around every once in a while. In 2014, Weingarten explained that many religious leaders liked to share the story as proof that beauty is everywhere. On LinkedIn, I saw the story being shared by recruiters as proof that you should look for a new job if your talents aren’t being appreciated at your current company. It’s a great story, and one that can apparently mean just about anything to anyone. It’s what might happen if Hermann Rorschach had written an Aesop’s Fable or two, and asked his patients to interpret that instead of an inkblot.

And I’m sharing this story with you for an entirely different reason. It’s as a warning and a reminder: Be careful about the data you cite when you tell stories like these.

Often, when I’m working with a new client, they’ll mention a tactic they want to try, but then mention a benchmark that’s wildly out of line with reality, and I have to work hard to help them readjust their expectations. A good example: A few years back, there was a story about a local newsletter that used paid acquisition to grow their list. The tactic is just fine — spending money on ads to grow your list is absolutely something certain publishers should try! — but this client kept quoting the cost to acquire an email address, not realizing that the publisher from the story was in a different country, and the amount quoted wasn’t in American dollars. They had the right idea, but somewhere along the way, the data had lost crucial context. (This meant that they were prepared to spend three times what they should have to acquire a single email address.) I’ve seen this sort of mistake happen with large publishers, with individual writers, and every type of newsletter creator in between.

So I’ll say it here again: Be careful about the data you cite when you tell stories like these — it might be wrong, and it might be leading you down the wrong path.

(And if you see someone sharing a story about a New York-based violist who made $20, do yourself a favor and don’t share it.)

———

At top, that’s a screenshot of one of the LinkedIn posts. As of this writing, there are over 40 pages of LinkedIn results for the story, all of which are nearly identical. There are even a few in different languages, which appear to have been copied into Google Translate and then copied over from there.