Figuring out how to handle emails while you’re on vacation isn’t easy. I’ve tried a few different strategies over the years — mostly, they haven’t worked.

But this past week, I tried something new: Transparency with a personal touch.

I told people when I’d be back and when they might expect a reply — the usual. But I added a personal flourish, explaining that I was out for a few days to celebrate my anniversary. A few years ago, I wouldn’t have included such a detail, worrying that it might’ve seemed too personal. Do people really care where you are? Don’t they just want their email answered as quickly as possible?

And instead, what I found was that so many people wrote back to my OOO with kind messages, and notes about the urgency (or lack thereof) of their messages. ”Enjoy your time off!” they wrote. “We’ll talk when you’re back.” I still wrote back to many of them, but felt far less pressure to reply while on vacation.

I’m planning on keeping this template: Telling people when I’ll be gone until, how frequently I’ll be checking email, plus a sentence about where I am or what I’m up to while I’m away. (If you’re in a big company, you might want to add a note about who else can help while you’re out of office.) The replies were so friendly, and I’m betting that several clients will ask, “How was the anniversary?” when we chat next.

Friendly, transparent, and a potential conversation starter? I think I’ve found an OOO format to use going forward.

———

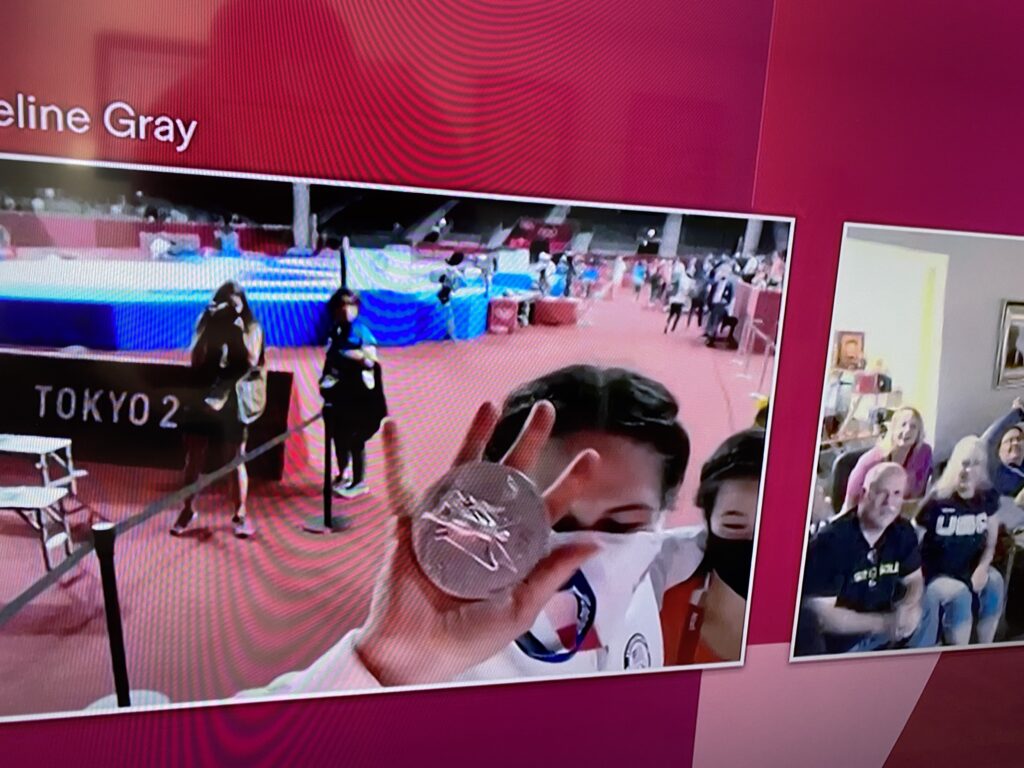

Above, that’s the full OOO message, plus one reply from a client.