If the buzz at South by Southwest is to be believed, all future communication amongst humans will be done via squares like this. (You may want to download this on your phone first.)

A Eulogy for Dexter, the Boykin Spaniel.

Like many people who I refer to as aunts and uncles, my Aunt Lois and Uncle Bobby aren’t actually related to me. They did, however, have the unfortunate privilege of living across the street from my family when I was growing up, and they had the poor sense to engage my mother in regular conversation. At some point, they were granted familial status, though I’m not sure exactly when.

In the time that they lived on Pollard Road, they had two dogs — one of whom I was apparently quite fond of, though he died before I’d even learned to walk — and another, named Dexter. Unlike all the other dogs in the neighborhood, all pure-bred from well-known lineages, Dexter was a Boykin Spaniel. Before he came to live with Aunt Lois and Uncle Bobby, he’d come from a long line of South Carolinian hunting dogs. Judging by Dexter’s ability to chase but never capture neighborhood squirrels, we didn’t think much of South Carolinian hunters.

Sometime around middle school, Uncle Bobby and Aunt Lois started wintering in Arizona, and they asked us to take care of Dexter. My mother, naturally, was delighted. I’m not sure what it was about Dexter, but she loved him. I’d always guessed it was Dexter’s coat, long and brown and curly, with the kind of poof not seen outside of one of my dad’s high school photo albums.

Dexter would stay with us for a few weeks at a time in the winter. Aunt Lois would drop off Dexter and his doggy bed, and then he would immediately decide to instead take up residence on our couch. He’d arrive smelling like an Herbal Essences commercial — Aunt Lois liked to pamper Dexter at a place called Bone-jour, a salon for suburban yuppies and their puppies — and he’d leave smelling of mud and filth and the salt that they use to de-ice roads. Mom loved Dexter, even when he smelled, and even though she usually made my dad walk him on the coldest days in winter.

Dexter died when I was in high school, and afterward, my mother was as sad as I can ever remember her being. I guess I don’t really remember how Aunt Lois and Uncle Bobby felt about his death; we often joked that Dexter had been “bark mitzvahed,” but we didn’t sit shiva for him after he died [1. UPDATE: Aunt Lois and Uncle Bobby have written in to say that, yes, they did sit shiva, though there may not have been a full minion present.].

I haven’t thought too much about Dexter since, but today, my boss sent me down to take some photos at a local dog show. It’s about what you’d expect from a dog show in Texas: there was an American flag hanging over the premises, but it only had about 23 stars on it. The dogs at the show were enormous, which seemed to explain why I had one of the only non-RVs in the parking lot.

They had about eight large rings set up inside, with dogs parading around each. I stopped by a ring of small dogs, then taller ones that looked like miniature llamas. I rounded over to a ring in the back, where three brown dogs with floppy ears were being judged. I heard a voice.

“They’re Boykin Spaniels.”

I looked up from my behind my camera. A woman at a judging table was looking at me and pointing to an official dog show program.

“They’re Boykin Spaniels,” she said again, now pointing to the ring.

I looked back at the dogs. The middle of the three was being coddled by his owner. The dog had those floppy ears that hung like the flaps on a Russian man’s winter hat. He had that shaggy coat. And he had this brown ring around his pupils, just like Dexter.

I looked back at the woman. “I know,” I told her. “I used to have one just like them.”

She seemed surprised, and I asked her where the dogs were from. She placed her thumb over one of the dog’s names. I didn’t see the name, just his home state:

South Carolina.

I looked back at the middle dog, and I wondered whether or not he’d ever been quick enough to catch a squirrel.

What Journalists Can Learn From Abraham Lincoln.

It’s been a while since my last installment of ‘What Journalists Can Learn From’ — it’s the first in this Jewish new year, actually — but I’ve just finished reading Doris Kearns Goodwin’s excellent “Team of Rivals,” and I saw more than a few lessons in Abe Lincoln’s words. Three especially pertinent thoughts for journalists:

Pick your words carefully: Here’s something I didn’t know about the Gettysburg Address: Lincoln wasn’t the featured speaker of the day. That honor went to Edward Everett, who gave what amounted to two hours of play-by-play about the battle of Gettysburg. Then Lincoln came up and delivered his 10-sentence-long Gettysburg Address.

After the speech was over, Everett told Lincoln, “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

There’s something to be said for brevity, for giving careful thought to each word. And for this, too: A man should start talking only when he knows what to say. [1. That, actually, is a quote from a former Washington Nationals beat writer.]

Give the audience time to react: With any new initiative, timing is key. With any really good idea, the creator needs to give the audience time to understand and adopt the idea. Take Twitter, for example. The site was around for more than a year before it started to really gain traction. But when it caught on, its growth was exponential.

Or, consider this incredible fact about the Gettysburg Address: when it was over, no one clapped. Lincoln took it as a sign that the crowd didn’t like his speech. Really, they were too astonished by what they’d just heard to even react.

The point is this: push the limits with your ideas, and give them room to grow. The audience might really like your idea, but they also might need some time to show their appreciation.

Brace yourself for any result: Of course, it’s important to remember that plenty of good ideas fail. So take the advice that one supporter gave Lincoln before the Republican primary in 1860. No one knew whether or not Lincoln would be able to pull off the upset, as he had entered the convention as a long shot. Lincoln had Presidential aspirations, but he had no idea if he’d even get a chance at the presidency. So his so supporter’s words? “Brace yourself,” he said, “for any result.”

For the uncertain world of modern journalism, truer words could scarcely be spoken.

A Porker’s Last Goodbye.

Earlier this week, my boss called me into her office to talk about a story I wrote last week about chicken fried bacon and the fried foods on sale at the San Antonio Rodeo. She told me that she liked my piece, but she wanted to see more perspectives. She wanted a fresh angle on the story. “Tell the story from their angle,” she said.

Earlier this week, my boss called me into her office to talk about a story I wrote last week about chicken fried bacon and the fried foods on sale at the San Antonio Rodeo. She told me that she liked my piece, but she wanted to see more perspectives. She wanted a fresh angle on the story. “Tell the story from their angle,” she said.

When she left the pronoun open, I decided to travel to north Texas, to talk to the voices behind that chicken fried bacon. This is that story.

DENTON, Texas — It’s not easy being a pig. But it’s even harder just being Wilbur.

“Well, yes, I know it’s happening soon,” he told me Tuesday. “I’m not an idiot. I saw ‘Food, Inc,’ too. I know it’s coming.”

For patrons at the San Antonio Rodeo & Stock Show, it’s Wilbur that will soon be coming to dinner. On food row, booths can’t keep corn dogs and chicken fried bacon in stock. Vendors are going through hundreds of pounds of pork each day, and with two weeks left in the Rodeo, they’ll need a lot more of Wilbur to keep those soon-to-be-pork-filled bellies happy.

But for an ordinary pig like Wilbur, the end of the road will be as bittersweet as the honey mustard he’ll eventually be served in.

“I always hoped that I’d end up on a Thanksgiving table, maybe as a honey baked ham” he said. “I didn’t think that they might ground me up and use me as the topping on a hot beef sundae.”

Wilbur’s not alone in that sentiment. There are hundreds of porkers here in North Texas, and the majority of these little piggies will not end up at market.

“I don’t have much of a choice,” Wilbur said. “I didn’t think I was going to grow old, to have some farmer wrap me in a blanket. But do I have to be slathered in ranch dressing when I go?”

Still, each new day brings Wilbur one day closer to his deep-fried destiny.

“You can fry me in batter. You can put a stick in me and coat me in cornmeal. You can slap me on a griddle,” Wilbur said. “I guess I can only hope that when I go, I’m delicious.”

A tear starts to crawl across his cheek, falling silently into the mud below Wilbur’s toes.

“That’s all I can ask,” he says.

The Blog Post That May Make Me The Butt of Your Jokes.

For the last 10 days, there has been something wrong with me. I have been slightly more irritable than usual. I’ve been twitchy at work. I’ve gone through long spells when my mind appears to be in a very different place.

Today, I believe I’ve discovered the problem.

I may be bleeding out of my anus.

Now, this is probably not the type of thing you’ve come to this blog to read, and perhaps you’ll be inclined to click away, to read about my mother or my experience with Kosher-approved pornographic advertising. I’ll understand.

I’ll admit that this diagnosis hasn’t been doctor-confirmed. [1. Though, you’ll admit, ‘slight anal leakage’ isn’t exactly a tough one to figure out.] But I’m still confident in it, partially because I can’t imagine many people have spent as much time thinking about their own ass as I have.

Some kids spent their childhoods looking up at the sky and guessing what each cloud resembled. My mother has stories of me, a two-year-old who’d come out of the bathroom describing in great detail what I’d just produced.

In fourth grade, when a family friend was asked what he was thankful for, he replied, “The toilet.” I just nodded in agreement.

At Hannukah, my siblings and I all hoped that mom and dad would gift us the latest edition of “Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader.” [2. We’ve collected just about every one of his volumes.] The toilet is where I learned to appreciate Dave Barry’s columns, where I studied the Wall Street Journal’s middle column and where I occasionally penned verse. [3. Poo-etry, perhaps?]

You get the idea.

Things get murky [4. Yes, there’s still time to bail on this blog post yet.] about three weeks ago, when I started to feel an odd twinge in my right shoulder. I went to the doctor. His verdict: a pinched nerve in my neck. He told me to take two-a-day of some pill that had more Xs in its name than I cared for.

That night, after popping the first of the pills, I felt something where I didn’t want to. Let’s call it an unwanted tingle.

I blamed it on the chicken fried steak I’d eaten at lunch.

But the tingle was still there on the second day. On the third, I started to feel that something was seriously wrong. I looked, of course, to my stool. [5. A technique, I learned, of course, via the musical episode of ‘Scrubs.’]

By week’s end, I was really worried. I was twitchy at work. I was tingly when I didn’t want to be — and where I didn’t want to be.

On day seven, I had to drop my laptop off at the store for some repairs — a note that would seem unrelated, except that afterward, I had a sudden urge to check WebMD for advice on my condition. I went to the public library to check my email, read the terms of agreement and decided that Googling anything beginning with the word “anal” might get me banned from all city buildings for the next year.

Finally, I got the laptop back. I checked first to make sure everything was in working order with my Mac — at least everything’s okay on this end, I told myself — and clicked toward my internal diagnostic confirmation.

Gastrointestinal problems? Check. Dermatological discomfort? Check. Special sensations? That might be one way to put it. Never had such an unspeakable tingle sounded more obscurer.

I walked over to the bathroom, where I’d left the bottle of pills on the counter. I felt up my shoulder, and I thought about my other twinge. Suddenly, the pain up top was tolerable.

The symptoms are now starting to subside, but the tingle was still there today. Also worth noting: I haven’t exactly figured out a way to casually mention my temporary condition at the office. It hasn’t been easy keeping my mind off of it, either.

In a chat with my boss this afternoon, I started to drift off. My boss asked if I was listening. I assured her that I was.

“I just can’t tell what you’re thinking about right now,” she said.

I squirmed a little in my seat, and I started to assure her that I had only two things on my mind. [6. I actually meant this new Twitter project and a meeting I had later in the day.]

Then I decided that I probably shouldn’t think too much about any number two.

When Voicemail Accidentally Serves as a Time Capsule.

The first thing I heard was a weird scratching on the phone, like aluminum foil was being rubbed against the receiver. Then I heard my mother’s voice, frantic.

“I must have just missed your call,” she said. This was last Thursday.

But I didn’t call, I told her.

That didn’t stop her. “No, Dan,” she said. “I just got your message.”

I didn’t leave a message, I told her, because I hadn’t just called. This seemed to clear things up on my end.

My mother kept talking.

“No, but I just got it. You said you were about to meet Hunter Thompson.”

I paused, the only way a man can pause when your mother calls and insists that you’ve just left a message that you did not leave explaining that you’re about to meet gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson, who you cannot meet because he died five years ago.

“You’re saying that you just got a message from me, claiming that I’m about to meet a deceased Rolling Stone writer?”

“Yes,” my mother replied, and without hesitation. This seemed like a perfectly normal thing for her to say.

I didn’t know what to say next. Of course, my mother did.

“You said you were sick.”

“I’m not.”

“No, in the message. Are you sick?”

I did not know what to say. To this point in my life, I had never had to deny the unlikely voicemail/I’m sick/meeting dead gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson trifecta. I started considering the possibility that my mother had been taking hallucinogenic drugs.

But thinking out the right way to respond to this line of questioning, something started to click. Back in the fall of 2005, I did get sick, and I did cancel on my friend, Andrew, who I was supposed to go with to meet a Mr. Wright Thompson — then a writer for the Kansas City Star, and now a reporter for ESPN. I asked my mother if the name Wright Thompson sounded familiar.

“Yes, yes, that’s the one. Are you supposed to meet him today?”

I explained that no, I was supposed to meet him in 2005, but I’d canceled because, well… I was sick at the time. Another pause. The timeline began to click into place.

“Do you mean to tell me that today, you just got a voicemail that I left for you five years ago?”

I started laughing, but my mother’s tone didn’t brighten just yet. I could hear her on the other end, still reaching for something motherly to say.

“You sure you’re not sick?” she asked.

And then, finally understanding the absurdity of the whole thing, she started to laugh too.

Wait, You People Still Speak to Each Other?

I haven’t been home to D.C. since I left for south Texas just over seven months ago. I keep up with some home friends via phone, and I caught up with a few earlier this month out in L.A. But for a good chunk of news and gossip from home, I rely on an email listserv that circulates amongst the guys from home.

So when I found out today that someone who we all went to elementary school with was joining an American football team in Spain, it seemed implausible. At work, I run three different Twitter clients at all times. I have a cell phone, a landline, a Google Voice number, an actively updating Facebook news feed and at least three email accounts. How the hell had I not heard about this already? [1. And as someone who considers himself a legitimate sports fan — and someone who spent half of 2008 living in Spain — how was I unaware that Spain had an American football league?]

Usually, when anything semi-important happens involving someone at home — say, two kids from my high school getting their Cal Tech-certified game theory paper on waiting for the bus published in the New York Times Magazine — I know about it. But this one had eluded the listserv, apparently.

I emailed into the group to see what the word was. A response came back: “not true, i — and i thought others — knew about this like a week ago if not more?”

A week? Three constantly updating Twitter feeds — and I was behind by a week?

I searched my Gmail account. No word of any Spanish football league teams. I emailed my friend back: Was there some alternate, super-secret listserv circulating?

Then the response came:

“The secret listserv you refer to is in fact the technologically archaic word-of-mouth.”

Oh.

Post-script: Since this post was published, everyone from home has been piling on. “I would like to amend your latest blog update,” wrote one friend. “You were behind at least a month. I knew about Carl in December at least.”

Another, studying abroad: “even i knew and i am in a third world country living in a rice village.”

And worst of all, from my mother: “Actually, I knew that.”

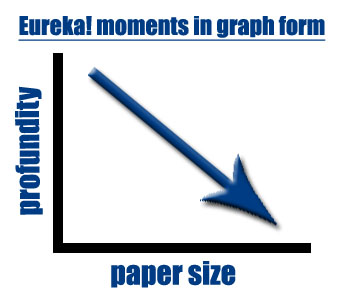

A Eureka! Moment: Why I Only Have Good Ideas When Tiny Scraps of Paper Are Around.

The revelation came to me in the moments before sleep, and I went searching for something to scribble it down on. All I could find was a small envelope on my kitchen table.

But what else could I be expected to write on in such a moment?

What hit me last night, what pulled me out of bed and sent me searching for any scrap of paper, was a simple truth: I only have good ideas when there’s barely anything around to write on.

I have owned dry erase boards that I’ve never used, oversized notepads that stayed blank and binders that held nothing.

But I’ve captured eureka! moments on cocktail napkins, scribbled genius ideas in the margins of newspaper columns and on business cards. I’ve rarely had success carrying around a notebook, with one exception: in the summer of 2008, when I had this bound, 3” x 2” pad that I covered every inch of with tiny thought bursts during my travels in China.

The more I consider it, the more the words jotted down last night on the back side of that envelope ring true: “The profundity of an idea varies in inverse proportion to the size of the paper it’s written on.”

Or, in words: the smaller (and stranger) the thing I’m writing on, the greater the eureka being written. [1. This may explain why I’ve jotted down great ideas on the inside of a paper towel roll but never on an actual, oversized paper towel.]

I’ve always kept these big legal pads around for the moments in which I’d need to fully flesh out an idea. But maybe it’s that a confined space — forced brevity! — is the key to innovation.

Shouldn’t the best ideas should be jotted down in their most basic form first before being carefully considered and expanded upon? Isn’t it only fair to let a spark turn into a slow burn, to let brief moments of genius turn into something of scale?

This is the kind of revelation that could force a change in lifestyle. I’ve started thinking about getting rid of all the big legal pads around my apartment. With the money saved, I could head to a local paper store instead and buy a stack of customized cocktail napkins. (“From the Desk of Dan Oshinsky,” they’ll read.)

That’s just one idea; I still haven’t decided what the next step is. But I’m not too worried. I picked up a tiny green receipt from a parking garage the other day. It couldn’t be more than an inch tall and two inches wide. I guess I’ll just have to keep it around and wait for inspiration to strike.

Dear Fans: Please Stop Storming the Court After Inconsequential Wins.

I’m sorry, because this doesn’t concern either journalism or my mother [1. Which, as you’ll note from the header here at danoshinsky.com, is the main focus of my blogging efforts], but this is too much.

I’m sorry, because this doesn’t concern either journalism or my mother [1. Which, as you’ll note from the header here at danoshinsky.com, is the main focus of my blogging efforts], but this is too much.

At right, delirious Michigan fans are celebrating a win that happened just this afternoon over the University of Connecticut Huskies. Most years, a win over UConn would be a huge deal. But not this year.

This year, UConn’s best win to date is over William & Mary, a Colonial Athletic Association team that has never made the NCAA Tournament. [2. N.B.: UConn has beaten two teams that have beaten Top 50 RPI opponents. William & Mary has won at Wake Forest and at Maryland. Notre Dame has beaten West Virginia at home.]

And I simply cannot stand by while college sports fans are storming the court after their team beats a team whose previous best victory was over a team that has never played in the NCAA Tournament.

Luckily, I happen to run in the kind of circles where such thoughtless court storming is frowned upon. A friend, Ryan Meyer — who you should get LinkedIn with here — started a chain of e-mails last week after the Clemson Tigers defeated his North Carolina Tar Heels, leading to a storming of the court from Clemson fans. He argued — and most agreed — that UNC wasn’t good enough to deserve a court storming.

What was decided upon is that there should be a set of rules for fans to abide by before storming a court.

Those rules are:

1) The opponent your team just beat is ranked in the top 10, and your team is unranked.

2) The opponent is ranked #1 in the country (your team can hold any ranking below #10).

3) Your team wins on an incredible buzzer beater.

4) Your team wins the conference championship. (For example, Siena fans storming the court as their team clinches an NCAA berth.)

5.) Your team was ranked as a 20-point underdog by Vegas oddsmakers.

6.) It’s a massive rivalry game that your team hasn’t won in more than decade.

7.) Your team erased a deficit of 20 or more points during the game.

A combination of several of the above can also justify a court storming. Take the last court storming that I was involved in: Feb. 9, 2009. My Missouri Tigers were losing by 14 points at the half to the Kansas Jayhawks, a hated rival; KU was ranked in the top 15; and Mizzou hit a game winning shot in the last three seconds for the win. It wasn’t a 20-point deficit (rule #7), or a top-10 win (rule #1) or the end to a decade-long drought (rule #6). But the combination of the three puts it over the top:

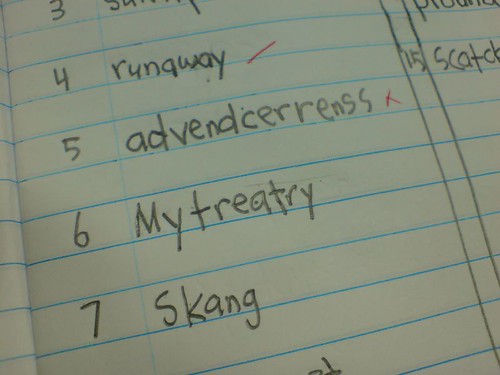

My Generation is Totally Screwed, and It’s All the iPhone’s Fault.

There is a very good chance that my generation is totally screwed.

Certain jobs are disappearing, and that’s a shame. It’s a shame that copy editors at newspapers are being fired. It’s a shame that accountants are being replaced by inexpensive computer software. It’s a shame that elevator operators are out of jobs (and have been for quite some time).

It’s a shame, but that’s all it is.

What’s terrifying — and maybe even dangerous — isn’t the loss of those jobs but the loss of certain skills. Technology has given us a wonderful ability to streamline our lives by pushing us past our cognitive limits. We have brains, yes, and when you sync that brain to an iPhone, you’ve got a tandem that’s capable of sorting through infinite amounts of hard data while freeing up space to make the difficult rational and emotional choices in our lives.

But what happens when we allow the machines to wholly replace certain skills? [1. The answer — as it concerns taxpayer dollars — is debated at great length in P.W. Singer’s “Wired for War,” a wise read about the future of technology in the military.]

This isn’t the first time that someone’s raised concerns about the loss of basic human skills, and it won’t be the last. Consider the classroom, where teachers worry about the impact of calculators on students. Who needs long division when a TI-83+ can do it for you? Who needs to master proper spelling when spell check will fix your mistakes?

This isn’t the first time that someone’s raised concerns about the loss of basic human skills, and it won’t be the last. Consider the classroom, where teachers worry about the impact of calculators on students. Who needs long division when a TI-83+ can do it for you? Who needs to master proper spelling when spell check will fix your mistakes?

Technology is evolving faster than we are. It will, I believe, come to a point where it overwhelms us.

The only question left is, What do we do when we get there?

I think of poor orientation skills due to GPS technology, poor researching skills due to Google and poor handwriting skills due to computers. I wonder how my brain will hold up under an inundation of information. On a daily basis, I multi-task while monitoring cable news (including the ticker at the bottom of the screen) and a cascade of news and links via Twitter. There’s no way my brain’s capable of processing it all.

Then I think a bit deeper: I wonder what will happen to our interpersonal skills now that Facebook is the link connecting friends. Chivalry is dead, but text messaging has taken communication to an instantaneous level that humans have never before experienced.

There’s one more level, and it’s the one that worries me the most. Maybe our brains will be able to evolve with technology. Maybe my fears will go unrealized. But what if — in 20 or 30 years — we find out that technology has come at a human cost?

As I write this, I’m sitting in a window seat on an airplane. It’s a prop plane, and the blades are whirring with remarkable noise. I can barely hear my friend, who is sitting in the seat next to mine.

Two rows in front of us, on the other side of the aisle, a man is listening to his iPod at what must be an incredible volume. He’s seven feet away, but I can hear every drum snare and every bass line escaping out of his headphones.

I’d like him to turn the music down, not as much for my sake but for his. I cannot imagine how many decibels must be pumping into his ears, but I know it cannot be a healthy number. At this volume, this man is literally listening himself deaf.

So I wonder: what will my generation do if iPod use wreaks permanent hearing damage upon us? And what will we do if we find that cell phones have been pumping cancerous waves of radiation into our brains?

In previous generations, health risks were slightly less complicated. Cigarette use was linked to disease and early death, and smoking rates have declined steadily since. But cigarettes were just a tool to relax the mind; they weren’t rewiring it. Even if we find out that certain forms of technology are detrimental to our health, putting down the smartphone might be a tough task, especially as we grow dependent on it as the brain we keep in our pocket.

What I’m saying is this: if technology doesn’t leave us behind, we still might have to find a way to leave it behind.

That might just be the scariest thought of all.