I am 30 years old, and I have so much more to learn. I’ve gotten the chance to work with amazing people at BuzzFeed and The New Yorker. I’ve led teams, launched products, and given talks at conferences. I’ve even been introduced on stage as an “expert” in my field.

But I am definitely not an expert. I’m only just starting to learn how to do this job, and learning how to build and lead teams that can do amazing work. I left my last job partially because I felt like I was no longer being challenged in my role, and I hated feeling like I wasn’t pushing myself to get better. There is a lot I can’t control in my work, but I can control the way I develop my skills and learn new things.

Complacency is the enemy of the work — and I’m determined to keep learning and keep growing.

Over the past year, there are certain things I’ve come to believe hold true. I know that my beliefs will continue to change. I know that I will change.

But here, at 30, is what I believe:

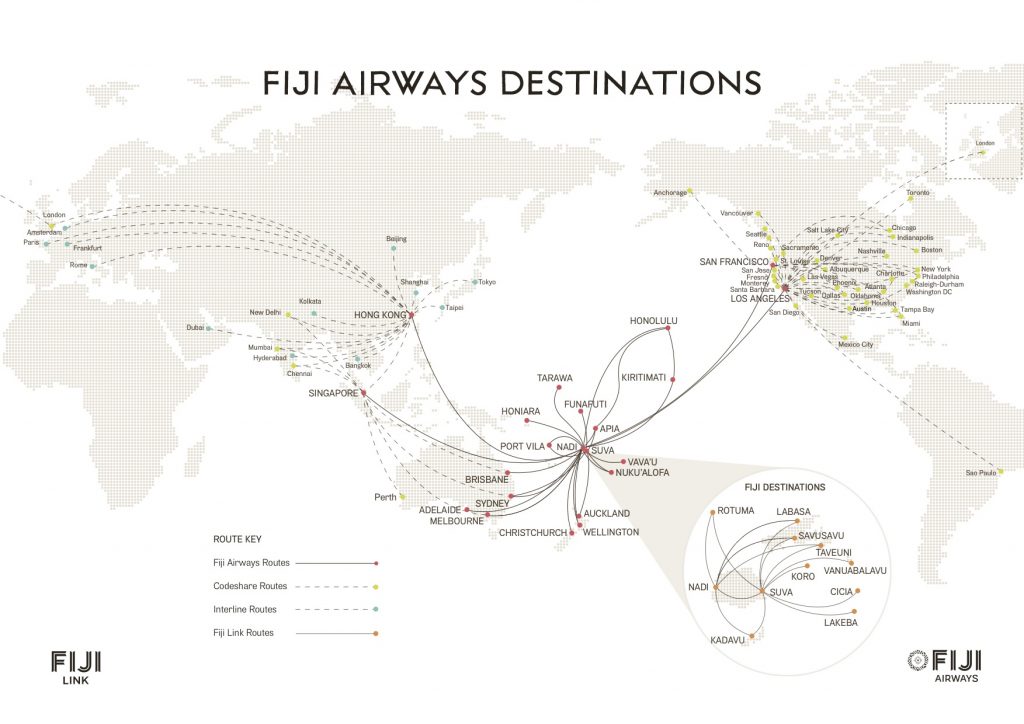

You don’t need to be able to predict the future — but it helps if you can see what’s coming around the corner.

Direction is more important than speed. It doesn’t matter how fast you’re going if you’re headed the wrong way.

The smartest people I know ask a lot of great questions, and I don’t think that’s a coincidence.

If you’re in a job where everybody else is smarter than you, you’re challenged every day, and you feel like a complete impostor, congratulations! You’re in the right place.

There’s always a way.

Challenge the ideas you hear about. Don’t take other people’s successes or failures at face value. Test them for yourself and see what works for you.

I need to get better at so many things: Not offering unsolicited advice. Asking questions even when I think I know the answer already. Saying “no” when I don’t have the time.

I am not particularly good at anything by myself. Everything I do well, I do with people I love.

One the hardest parts of getting older is deciding what you really want to spend your money and time on, and actually sticking to it.

The best nights out are the most unexpected.

Everything is better shared.

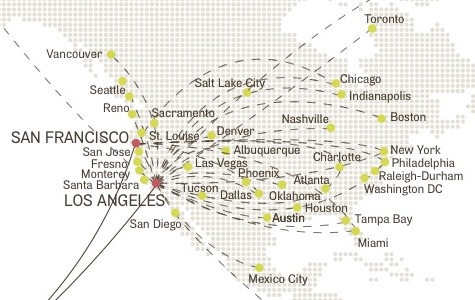

Four magic words that will change the way you fly: “Can you help me?” People can be so rude when they travel. Just be kind, and ask for help. It’ll take you far.

Overcommunicate. Don’t assume that people around you are on the same page. Make sure they know what’s expected of them, and what they expect of you.

Your plan isn’t much of a plan if you can’t get your team to buy in.

When you’re making a big decision, lay out all the options, get all the information you can, and make the best choice with what you have. It won’t always lead to the right outcome, but you don’t have much control over the outcome. Worry about what you can control: the process, and the work.

And most of all: Every day, I try to be a little more: more enthusiastic, more helpful, more loving. I’m so lucky to have married a woman who is all of those things — and, yes, even more. I love you more than ever, Sally.

———

That photo at top was taken by the @DigitalBrisbane team.