Here is what happens when I hear about news indirectly — basically, when breaking news gets to me secondhand:

Here is what happens when I hear about news indirectly — basically, when breaking news gets to me secondhand:

1. I run to a computer.

2. I open up the nearest Twitter client.

3. I search for the news that I’ve just heard and try to find confirmation that it is either true or false.

In short, Twitter is my first source for news verification. It usually has details on an event long before traditional news outlets can get a full story up online.

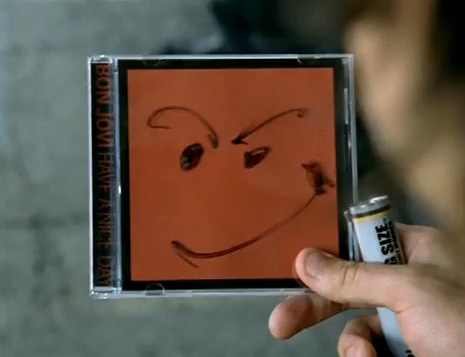

But consider what happened to me Saturday night. I see this Facebook update from a friend, a Springsteen fan. It says, “RIP Big Man.”

And I immediately log onto Twitter to search for news about Clarence Clemons.

Except — that’s exactly the wrong place to go for something like this. Twitter is where death hoaxes go to really get rolling. On Twitter, someone impersonating @CNN has announced Morgan Freeman’s death. On Twitter, we’ve seen Adam Sandler and Charlie Sheen and even Mick Jagger die, only to find out hours later that they’re actually still alive.

Death hoaxes aren’t even the worst of it. Sometimes, we’ve got news hoaxes going around. Like the one from real Washington Post columnist Mike Wise. Or a new hoax from a guy who claimed to be a college basketball recruiting expert with inside information. Turned out he wasn’t. Didn’t stop his fake news from getting real attention, though.

What I know is this: we need a way to verify these news-related tweets. Twitter took a big step forward when it introduced verified accounts. But it needs to go a leap beyond that, I believe.

So here’s an open call to the Twitter team: Want to make your corner of the Internet one that actually prides itself on accuracy? Want to make your product the thing that people actually trust?

Start verifying tweets.

Not Twitterers (or tweeple, or tweeps). Go verify individual tweets.

And you’re not going to like how I think we should do it:

With humans.

❡❡❡

Hear me out. I’m talking about Twitter, one of the biggest and most powerful news reporting tools on the planet, employing a team of real, actual humans. Humans who make phone calls. Humans who verify information independently, and don’t just Google something to find out if it could be true.

In the past, we called such humans “reporters.” I’d be okay with using that phrasing again.

It’d work like this. Twitter would bring its own team of reporters in house. They’d monitor activity on Twitter. They’d see what’s trending and what’s bubbling just below the surface. And when something big breaks — say, an #RIPBobSaget hashtag — the reporting team would break into action. They’d make calls. They’d independently verify Mr. Saget’s status. If it turns out Mr. Saget was, in fact, not killed in an awful wakeboarding incident in the Swiss Alps, the Twitter team would move to quell the rumor by:

A. Posting a breaking news update at the top of the Twitter page devoted to the hashtag.

B. Creating a push notification specifically targeted to those using the hashtag — or discussing Bob Saget — to inform them of the truth.

That’s the starting place.

❡❡❡

But what if Twitter went further? What if Twitter created a specific channel for breaking news, where it could publish breaking news tweets in real time? Think the Google News homepage mixed with the instant refresh technology of TweetDeck, with all news curated by the Twitter reporters. Wouldn’t that be a must-bookmark?

Think of it this way: Why wouldn’t Twitter HQ want to better utilize Twitter as the breaking news service it already is? Give us headlines. Give us the news ticker, Twitter style. Give us a verified account with trusted, we-actually-made-a-call-and-know-this-to-be-true news. Call it @TruthSquad. Call it @VerifiedNews.[1. Just don’t try to combine Truth + Twitter, because you’ll end up with something like @truthitter. Not a flattering name.]

And don’t say it wouldn’t pay for itself. When an earthquake hits Los Angeles, and Twitter’s in-real-time news page is posting links and Twitpics, you don’t think the New York Post would pay $10,000 to get their quake story posted at the top of the Twitter breaking news page? You don’t think they’d like the extra million hits they’d get just from Twitter referrals?[2. Speaking of which: Celebrities would also be a great source of income for Twitter. When you crash your car, your insurance company pays to fix the damage. If someone starts a Bob Saget is Dead rumor, why can’t Saget get social media insurance to recoup the damages to his brand name? Pay Twitter a little, and Twitter insures that when false information gets out there, they’ll get the real information into the hands of users who care about celeb news.]

Now, do note: there is no way to verify off-the-record or on-deep-background information passed along from some reporters. If @ESPN says, “Sources tell @ESPN that Michael Jordan will be coming out retirement to play for the Miami Heat,” the Twitter team isn’t going to be able to confirm that. They don’t have ESPN’s sources. But they can confirm certain news.

An official Twitter team of reporters can stop hoaxes. They can get truthful information out to consumers.

They can make Twitter the place for trusted, breaking news.

Traditional media can’t necessarily serve this role as the gatekeeper for real-time truth. Tell me again why can’t Twitter do it itself?

My little sister graduated from college this week. We went down to celebrate graduation with her. We filed into the school’s basketball arena on Thursday. We sat and watch the processional. An orchestra played. A Dean spoke. Hands clapped, and parents ‘Woo-Hoo!’-ed, and mostly, we just sat, unbelievably proud of my little sister.

My little sister graduated from college this week. We went down to celebrate graduation with her. We filed into the school’s basketball arena on Thursday. We sat and watch the processional. An orchestra played. A Dean spoke. Hands clapped, and parents ‘Woo-Hoo!’-ed, and mostly, we just sat, unbelievably proud of my little sister.