I’m getting married in three weeks. And: I’m excited! I can’t wait to see so many people I care about in one place, and I cannot wait to finally say “I do” to the woman I love.

Of course, there is this one thing that’s been nagging at me for a little while, and I want to say something about it out loud:

There is a typo on the welcome note that’s going in everyone’s gift bags. And I can’t do anything about it.

Let me explain.

When you plan a wedding, you end up making a thousand tiny decisions about stuff you never knew you needed to care about. From one big decision — Will you marry me? — comes a thousand tiny ones: Is this the right font for us? Should we upgrade the napkins? Are we making the best possible choice about chairs? (Side note: Did you know those chairs you see at every wedding have a name? And did you realize you have to pay more for those fancy chairs, even though they’re kind of uncomfortable? Weddings are weird like that.)

You end up making a lot of decisions, and you end up with a shocking number of moving parts for a single event.

Which is why, eventually, you end up realizing something: The more things there are, the more things will go wrong.

If you make a thousand tiny choices, a handful aren’t going to go the way you wanted them to. It happens! The caterer is going to forget about that cheese you specifically requested. The DJ is going to play a song you didn’t want them to play. The bouquet will include a flower you didn’t ask for.

Or, yes: You’ll make a tiny typo on a note going in the gift bags at the hotel. (I forgot a comma! I should proofread more closely next time! I’m sorry!)

Say it with me: The more things there are, the more things will go wrong.

That’s how it goes with weddings, or with any big project you work on. It’s inevitable. The more complicated a project gets, or the more people who get involved, the more likely it is that things are going to go wrong. Mistakes always get made. The hardest thing is accepting the mistakes, and being willing to keep your focus on the big picture and not the little details.

Most only notice the big picture anyway.

I’ll tell you a quick story. It’s about my bar mitzvah. 48 hours before the big day, I stood in an empty synagogue with my rabbi and my parents, practicing my Torah portion. I’d spent months preparing for the day, and this was the final rehearsal before it actually happened.

But during that rehearsal, I flubbed a line in Hebrew — a language, it’s worth noting, that I don’t speak! — and got completely flustered, ran to the bathroom, and locked myself inside for 20 minutes.

And I cried.

When I finally came out of the bathroom, my rabbi gave me some advice: If you screw up a line, it’s OK! Just go back to the beginning of the line, and read it all over again. Nobody will ever notice.

And on the day of: I did screw up a line. But I went back to the beginning, and read it all over again.

My rabbi was right, of course: Nobody noticed. If anything, the family members who could read Hebrew just assumed that I was supposed to chant that one line in Leviticus twice.

Again: The hardest part of mistakes is learning to let them go.

So as for that missed comma on the note in the gift bags: We’ve got enough time to fix it, but… we aren’t going to. It’s just a missed comma, and this is the first of many, many little details that we’re going to mess up.

The big picture matters far more. Yes, we’ll remember the tiny flubs. But we’re trying to stay focused on giving the rest of our guests a whole night they’ll never forget.

— — —

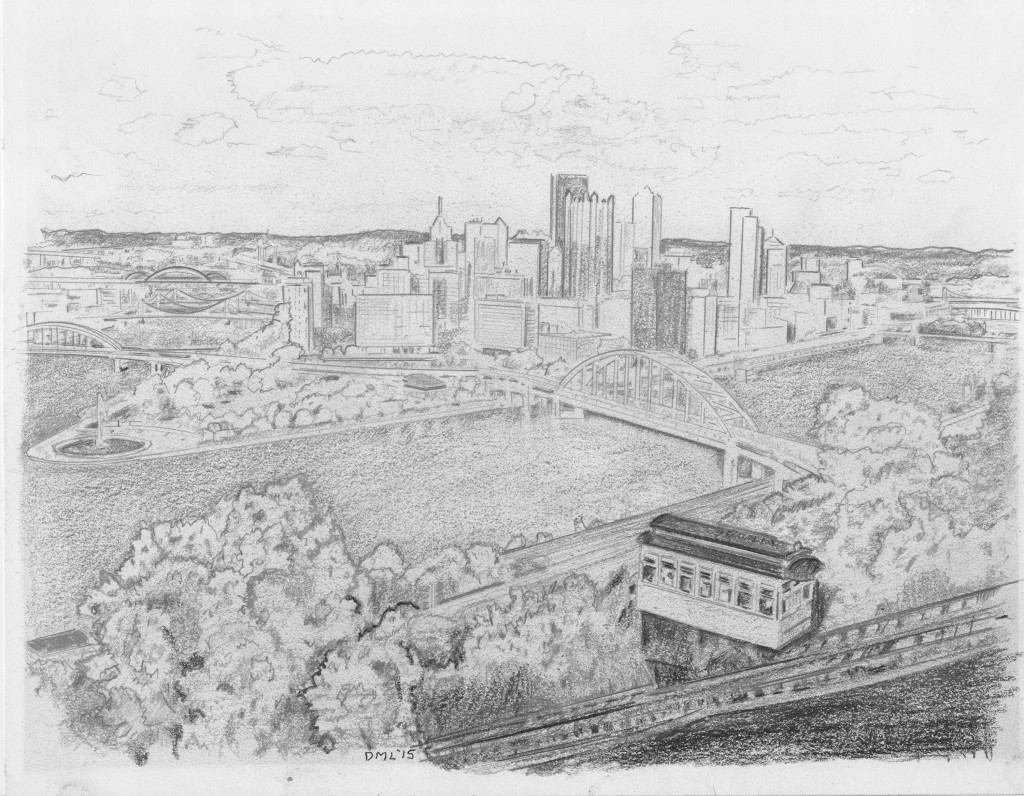

That drawing is by my soon-to-be father-in-law, Dave. (He’s quite talented!) It’s of downtown Pittsburgh, where we’re having the wedding.