I can’t believe I’m saying this, but: I completely agree with Simon Cowell on something.

You remember Simon, of course. He was the loud, controversial judge from “American Idol”, and the reason even I tuned in to see that show’s finales.[1. I still stand by my Ruben Studdard vote.]

Anyway, he said something in an interview with the New York Times last weekend that got me thinking about the way we define failure. He was asked about one of his other shows, “X Factor”, and he said:

“I read a book once about Coke and Pepsi and it was called ‘The Other Guy Blinked.’ And we blinked. We thought 12 million [viewers] was bad. Now, I’m thinking, ‘Christ, if I could launch a show with 12 million today, I’d be a hero.’ But we beat ourselves up so much about it and we changed so many things. The show became unrecognizable. I blame myself, but we made crazy decisions. We didn’t treat it like a hit. We treated it as a failure. I wasn’t aware the market had gone down to that level so quickly. I was in this La-La Land head space of 30 or 40 million and I thought 12 million feels terrible.”

That last sentence is the big one. What must it be like to launch a huge TV hit and still feel like a failure?

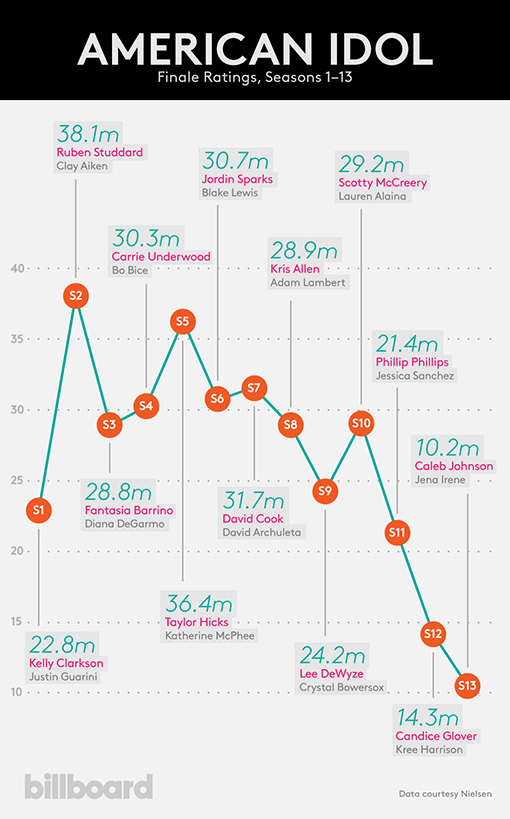

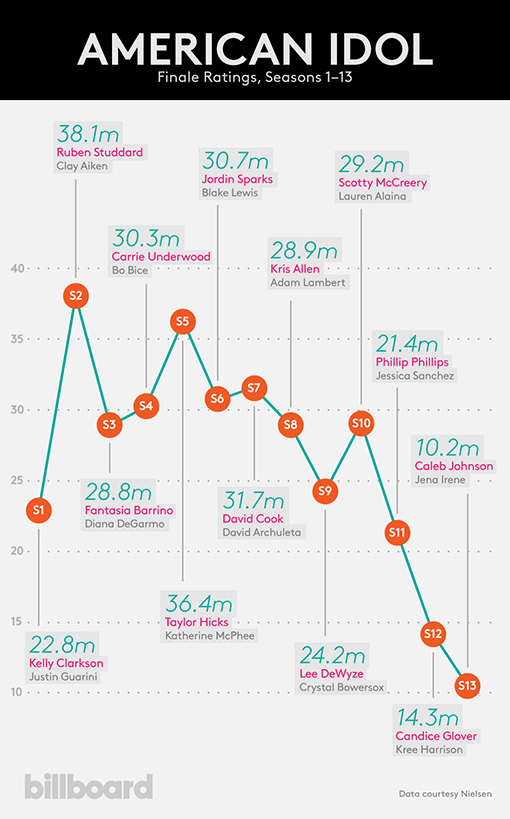

It makes sense if you think about where he’s coming from. Simon’s first U.S. hit, “American Idol” once drew 38 million viewers for a finale. But then the numbers dropped, and never fully recovered. Here’s what it looked like, according to Billboard:

Even into it’s thirteenth season, the show was still drawing big numbers for finales. But it wasn’t what it had been a decade earlier.

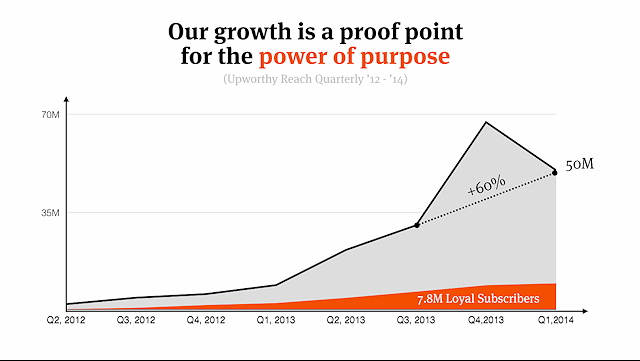

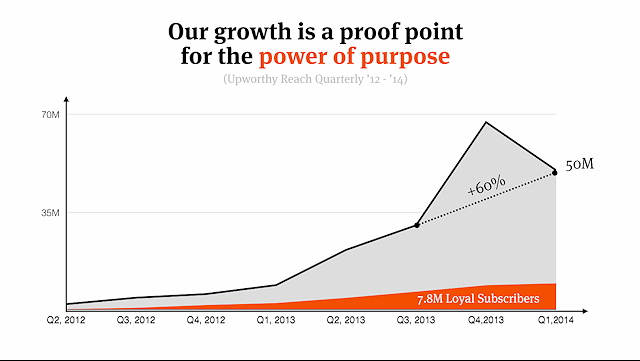

Keep that chart in mind for a second. Now look at this:

That’s a chart that Upworthy, one of the fastest-growing publishers of the decade, showed off publicly in 2014 as they grew from zero to nearly 70 million unique visitors.[2. I’m going to pick on them for a second not because I dislike them — I actually think they’re doing really good work! — but because their last 4 years have been so well documented.]

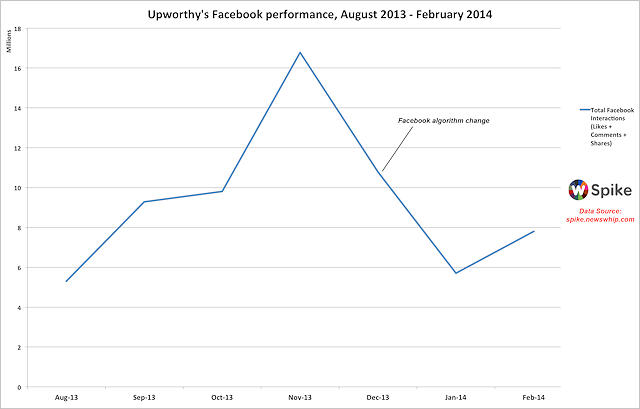

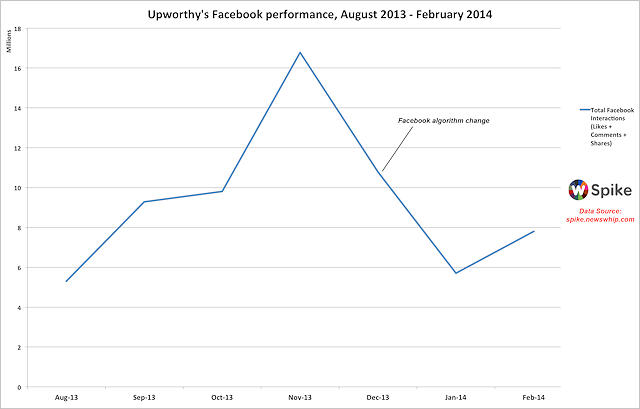

Now let’s zoom out for a second:

That’s what it looks like when you rely entirely on another entity for success — in this case, Facebook — and then that business changes they way they do business. Facebook changed their algorithm, and Upworthy went from 70 million uniques to 50 million uniques, and kept dropping. Afraid that they could go from 70 million to nothing just as fast as they’d gone from 0 to 70, Upworthy changed their publishing strategy, and then changed it again. Now they’re doing what a lot of media companies — including BuzzFeed, where I work — are doing: Following the lead of distribution channels and hoping that the Facebooks and Snapchats of the world take us all to profitability. We’ll see how that strategy plays out over the next 3-5 years.

But what I’m most interested in is what happens to the people on the inside when a rocket ship like Upworthy starts to level off. That’s where Simon’s quote comes to mind. Read it again:

“We didn’t treat it like a hit. We treated it as a failure. I wasn’t aware the market had gone down to that level so quickly. I was in this La-La Land head space of 30 or 40 million and I thought 12 million feels terrible.”

“American Idol” was a rocket ship, too. It grew from nothing into a national phenomenon. But it didn’t last forever. The numbers dropped, and “Idol” merely became a big and hugely profitable TV show — merely a big and hugely profitable TV show! — not a supernova.

It’s all about perspective, though. What “Idol” built — and “X Factor” did, too — was a huge success, but from the inside, it clearly didn’t feel like that. And when you’re on a rocket ship like “Idol” or Upworthy, or the one I’m still on at BuzzFeed, it’s all about perspective. They’re about understanding that the ride up doesn’t last forever, that leveling off can be a normal course correction, that from where you stand — 12 million viewers, 50 million unique visitors, whatever — you’ve still built something impressive. You might feel like you’re losing ground because you’re not meeting your own expectations, and then you look around and realize where you actually are.

Maybe it’s not the up-up-up ride you thought, but you’ve still reached rarified air.

One last anecdote, from one of my favorite singer-songwriters, Todd Snider. I saw him tell a story once about Hootie and the Blowfish, a band he opened for back in the ‘90s. He talked about how their first album sold 16 million copies. Their second sold 3 million. Their third sold a million. They were a rocket ship that burned out. People called them a failure.

And it’s at this point in the story that Snider said, “Their third album still sold a MILLION copies! Sign me up for that kind of failure!”

It’s worth saying again: After “Idol” started to fail as a show, it still ended up running for 15 years. Simon Cowell launched two more hit shows. Upworthy is one of the biggest publishers in the world. Hootie sold several million albums. Darius Rucker went on to win a Grammy.

Yeah, sign me up for that kind of failure.

———

That photo of a rocket comes via SpaceX and Unsplash.