I had a moment today where I had to ask myself: What the hell am I doing today?

This sort of question isn’t all that strange. I do this every once in a while: I wonder about what it is I do, and whether or not I’m doing the right thing right now — normal stuff most people in their 20s worry about.

But this time, I wasn’t thinking about what I’m doing with my life. This morning, I was literally thinking: What the hell am I doing today?

See, when I started at BuzzFeed, I was the only person working on newsletters. I was the guy designing the newsletters, creating the templates for the newsletters, launching the newsletters, doing promotion for the newsletters — oh, and writing the newsletters. By the end of 2013, I was writing 30+ newsletters a week.

It was a lot.

To get it all done, I created a laundry list of day-to-day tasks for myself. I had routines for every day of the week. When I got those tasks done, I had a good day. When I didn’t, well…. that never happened. The newsletters always got out. The work always got done.

In 2014, the newsletter team grew to three people, and the tasks changed. But I still had my Monday routine, and my Tuesday routine, and my Wednesday, and my Thursday, and my Friday. Every day, I had to get it done.

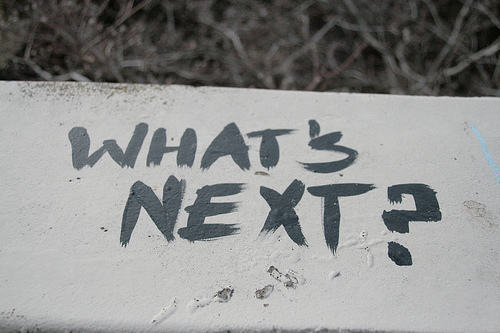

But now this year, the team’s grown to 5, and I gave away my tasks to other members of the team — all of them. And suddenly, I started waking up trying to figure out what the hell I was supposed to do with my work days.

I’ve done the same things pretty much every day of the week for the past two years. So now that I’ve got a brand new role that’s still being defined… now what?

After a week or two of quietly floundering at work, I realized I had to get some structure back into place. So I sketched out my days in a pretty simple way:

Mornings are my time. They’re for going to the gym, writing, and working through big ideas. If I’m going to do something for me, it’s happening in the morning.

Once I get to the office, that’s my team’s time. That’s when I need to support my team, brainstorm with them, help them work on projects and launch stuff, take meetings, and make things happen to get the team to the next level. When I’m at work, I’m there for them.

What I hope is that in the long run, this’ll help me figure out when I should take on certain tasks. The structure is so important for me — it defines my day and makes it clear what roles I need to play during the day. There’s still a lot of freedom for me, and I like that, but for now, I need that structure to help me get the work done every day.

Here’s to that structure — and to getting back to doing the work.

———

That photo at top comes via Flickr.