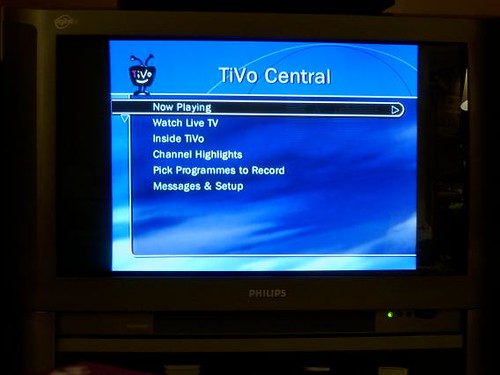

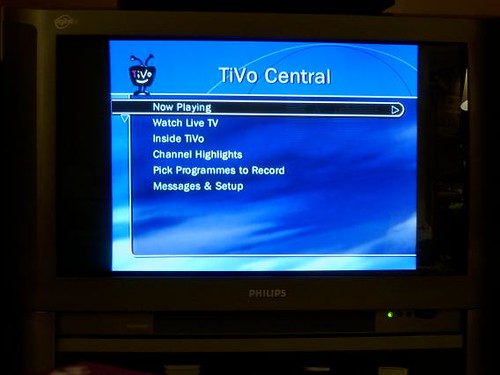

In 2002, the company that measures how many people watch television decided to do something experimental: They started measuring how many viewers were watching TV shows via something called TiVo, a personal recording device that had come to market three years earlier.

Nielsen Media Research, the ratings company, had been measuring TV ratings since the 1950s. But their ratings technology only accounted for viewers who were watching shows at the very moment the shows were airing live. If a viewer decided to save a show to his or her TiVo, and then watched the show at a later time, that viewer didn’t count towards the overall ratings for the show.

It’s about this time that ratings for some shows started to decline. TV executives had their suspicions about the declining numbers. They felt their shows were still being watched, but they were being watched via TiVo, and Nielsen wasn’t counting these viewers. As far as the Nielsen ratings were concerned, watching via TiVo was the same as not watching at all.

And since the value of television advertising rises and falls with TV ratings, ignoring actual viewers was costing TV channels money. So they pressured Nielsen to add these TiVo viewers into the overall ratings picture.

This all sounds kind of ridiculous today — I mean, really, how could Nielsen have just ignored these viewers for years? — and that’s because it is ridiculous. Eyeballs are eyeballs. They should all be counted equally, whether they’re seeing a show when it first airs or a week later via TiVo.

It’s also why it should confuse you when I tell you this: News publishers today are making the exact same mistake that Nielsen did a decade ago.

❡❡❡

The world of modern news publishing isn’t all that different from the world of TV. Like TV, publishers rely heavily on advertising to sustain their operations. Put simply, the more readers a news site has, the more money it typically can charge advertisers.

TV ratings center around two main numbers: Rating (the number of TVs watching a show compared to the total number of TV households) and share (the number of TVs watching a show compared to the total number of TVs tuned in at that particular moment).

Online news metrics are slightly different. Three stand out:

-Time spent on a news site

-Pages read per visit to that site

-Unique visitors to the site

All three are important. But all three also fail to accurately measure a vital chunk of their audience.

❡❡❡

About two years ago, a Twitter hashtag kickstarted a small but influential movement for readers. The hashtag was called #longreads, and it promoted interesting stories of 1,500 words or longer. A story of that length might take anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours to read. Hence, the name #longreads.

The problem is, #longreads disciples don’t always have the time to read these stories at the moment they arrive in an inbox or pass through a Twitter feed. Sometimes, readers need to save a story for later.

It’s not a coincidence that just as #longreads was starting to grow, a handful of sites popped up to serve that very need. These sites enable users to time-shift stories to a time/place when the reader actually has time to read said story.

It’s not a coincidence that these are known as time-shifting tools. That phrase first became popular with the advent of TiVo.

There are three big sites that allow users to time-shift stories: Instapaper, Readability, and ReadItLater. All three take user-saved stories and store them on the site’s own servers. When readers want to read something, they head over to their site of choice (or the site’s app) and search through their queue for something good that they’ve already saved. The reading experience happens there, not on the publisher’s site.

So this is the good news for publishers: A community of avid readers has access to thousands of new stories that they otherwise wouldn’t see, and these readers are reading and sharing these stories. They’re passionate about this type of reading experience. These are the kind of readers who read so much that they need a TiVo-type tool just to hold all that they want to read.

This is the bad news for publishers: Readers are spending an awfully long time reading great stories, but they aren’t doing it on the publisher’s site.

A reader like me might spend half an hour reading a #longreads essay or exposé, but all the publisher sees is the handful of seconds I spent on the story before bookmarking it for later. Some of the most engaged readers are going, essentially, uncounted.

❡❡❡

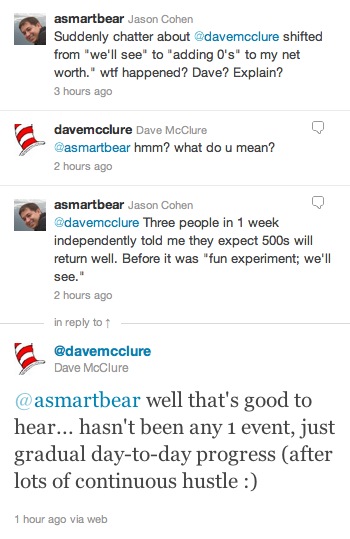

Which brings me around to some data that ReadItLater — one of the three big time-shifting sites — published last week.

The data was mined, in part, by a guy named Mark Armstrong. It’s no coincidence that Mark was the one who started the #longreads hashtag. (Now, he’s an editorial advisor for ReadItLater.)

The data shows that ReadItLater has some powerful tools for measuring user engagement with a story. They can measure which authors and sites are most popular. They can measure which stories get put most often into the queue, and which stories get read the most once they’re put in the queue. And that’s just what we learned from this first data set. Just wait until ReadItLater really starts digging.

Unfortunately, this is vital data about power users that publishers aren’t factoring into their metrics. These users aren’t being counted in the overall numbers, and we need to start counting them. Core users are just being ignored, simply because their reading experience is happening on a different server.

Don’t underestimate the size of this audience, either. ReadItLater has four million users, and they’re hosting just a fraction of the time-shifting audience.

Right now, in the publishing community, we have opportunity to prove that these sites have the same type of impact on overall numbers that the TiVo did on Nielsen’s TV numbers. We need to start accounting for this time-shifting in our metrics.

If we don’t, we’re just ignoring some of our most engaged users, and we’re costing ourselves money.

❡❡❡

One other thought: The three services I mentioned do essentially the same thing. But not all three will last. There’s a reason that VHS and Betamax didn’t co-exist for a decade; there’s a reason why Foursquare beat out all the other location-based services. The market will pick a winner.

And I don’t think I’m going too far out on a limb to say that the winner will be the one that:

A.) Helps publishers make money, and

B.) Shares their data with publishers to make content more measurable, and therefore more valuable to advertisers.

The question is, Who within this market will step up to do just that?

❡❡❡

One final quote on the matter:

“Time-shifting will be something more people are really comfortable with. We never know if the technology is going to sizzle or fizzle, but you can’t wait until it takes off before you say, ‘Hey, maybe we should measure this.'”

Yeah, you guessed it: That quote’s from 2002, in an article about Nielsen and the DVR.

But here’s what I’d like to point out: You don’t have to change even a single word from that quote to apply it to today’s time-shifting tools for reading. The call to the action is the same.

Here’s my plea to publishers: It’s time for us to stop ignoring active readers. We’re in the business of telling great stories. We shouldn’t forget about those who love to read them.

Let’s start measuring the true reach of our stories.

[ois skin=”Tools for Reporters”]