In 2010, while reporting in Biloxi, Mississippi, on the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, I stumbled upon this story:

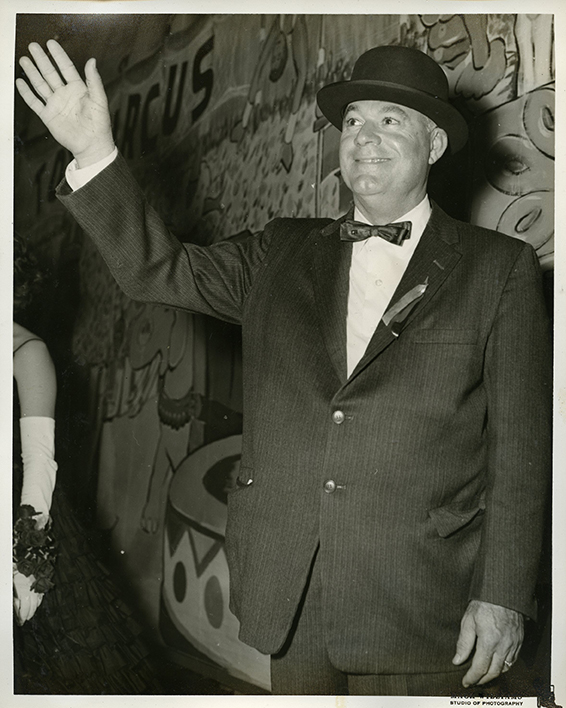

A century earlier in Biloxi, there was a man of some renown named Walter Hunt. He didn’t go by that name, though — in town, locals called him Skeet.

Skeet was quite the figure in Biloxi. At age 26, he’d become the youngest alderman in the city’s history. He’d been the grand marshall of the Mardi Gras parade. Later in life, he’d move to Washington, D.C., and become a captain of the Capitol Police. (He’d ship up fresh seafood from the Gulf on trains when he was trying to curry favor with members of Congress.)

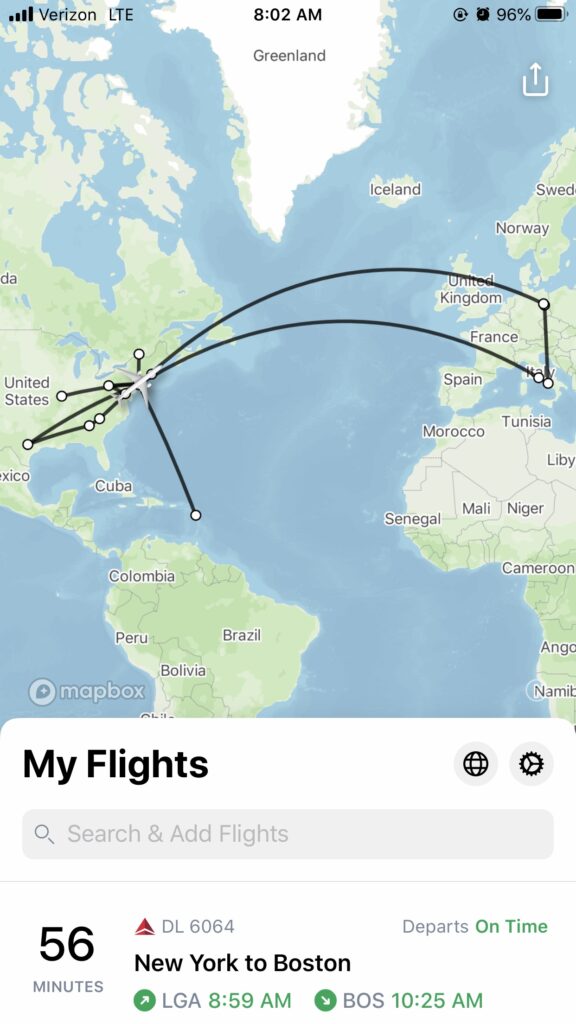

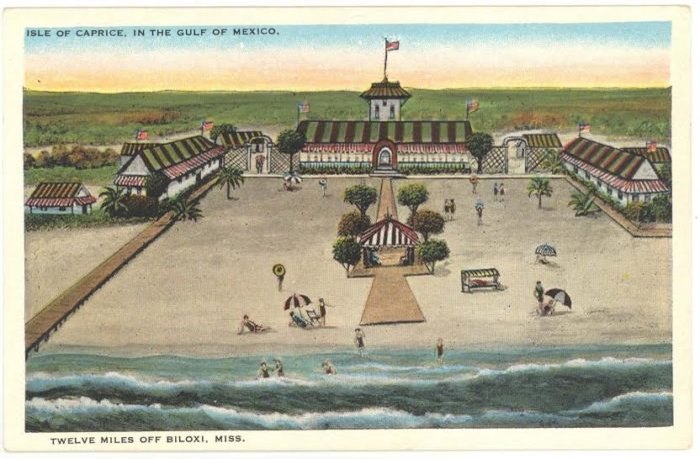

But in 1925, Skeet took a gamble. He’d inherited an island, twelve miles out in the Gulf of Mexico, from his grandfather, and decided to build a casino on it. He called it the Isle of Caprice — “caprice,” as in, a sudden, unpredictable series of changes.

For a few years, things went well for Skeet and his casino. Business boomed. In 1927, an estimated 40,000 visitors came to the island. Ethel Merman played the lounge.

Then in 1931, Skeet’s team went out to the island to get the casino ready for the summer season.

But the casino wasn’t there.

What must it have been like to be a member of the crew, floating out in the Gulf of Mexico, and suddenly realizing that Isle of Caprice had been built not on an island, but a sandbar? What were they thinking as they discovered that over the winter, when the sandbar moved, the casino had sunk into the Gulf?

All the staff could find was a single pipe sticking out of the water, still connected to a well that had been dug deep into the ground. Everything else was gone.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about Skeet’s story. I’m thinking about all the things that will be different once we’ve emerged from this pandemic. Businesses will change, cities will change. We don’t know what life will look like in a few years, but things will almost certainly be different.

Right now, that once-solid ground is shifting underneath our feet. Standing still isn’t an option. It’s up to each of us to recognize that we need to move with the tides — or we will sink.

———

At top, that’s a postcard from the 1920s of the island. Below, a photo of Skeet from a Mardi Gras parade.