I’m on a bus on the New Jersey Turnpike, heading home. I’d say we’re driving north, but that’s not quite right — we’re not moving. There’s a huge crash on the road, and traffic’s stopped. What should be a four-hour drive from Washington to New York will take nearly six.

It didn’t have to be this way.

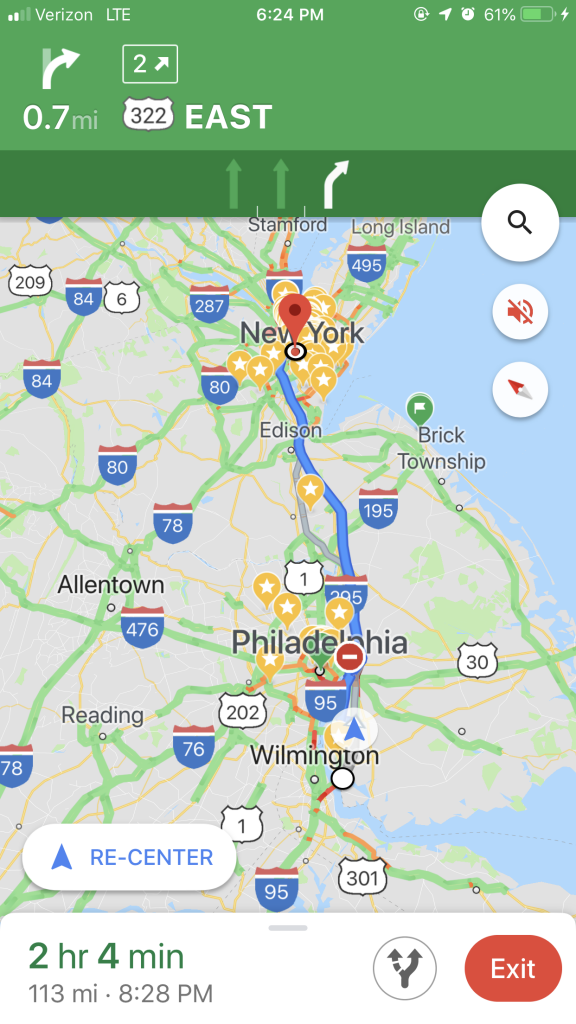

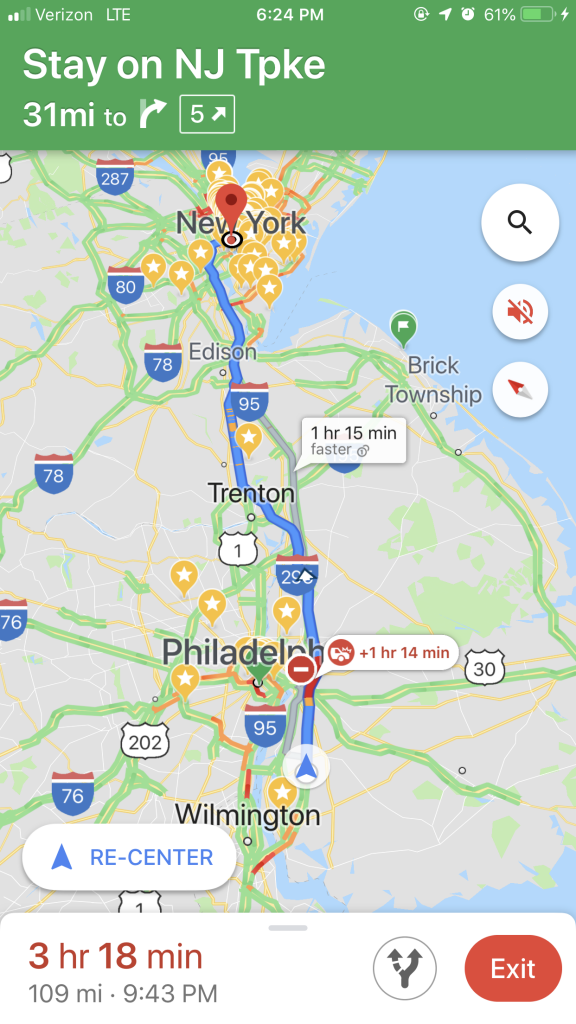

Whenever I take the bus home, I keep an eye on Google Maps. I’m not driving, so I don’t need to know the best route home, but I do like knowing when we’ll arrive. The bus is fine — it’s cheap, and it gets you where you need to go, but it’s not the most comfortable way to travel. Still, I find that as long as I know when it’ll all be over, I can maintain a level of sanity. Sure, it’s a little too hot in here, and the people two rows up are talking a little too loudly — but there’s only an hour left!

On this trip back, though, I saw something I’d never seen before on Google Maps: a warning that we were about to drive into the massive traffic jam caused by the crash that we’re now stuck in. Google Maps made it pretty clear: We had to get off, or we’d end up in this jam. It suggested multiple alternate routes, any of which would save us upwards of 75 minutes. Just off the bridge, I watched as dozens of cars in front of us suddenly veered to an exit, guided by Google Maps to a better route. On the Turnpike, signs above the roadway warned: “CRASH AHEAD — SEEK ALT ROUTE.” Soon after, more cars — clearly noting the sign, and having opened up Google Maps — found the exit ramp.

Our driver plowed onward — into the jam.

All of this has me thinking about the mistakes we make in life, and what we learn from them. When you’re young, you’re going to make mistakes. Small ones, big ones, dumb ones — you’re going to make them all. You’re going to do things that make you look back and go, What was I thinking?

There will be people in your life who try to steer you away from those mistakes. Often, you’ll ignore them, and make them anyway. Some lessons you just have to learn from experience.

But what I’m most curious about is how you react to those mistakes. It’s OK when you screw up — that’s going to happen! But what happens next? What do you do differently next time? What conversations do you have next to help you learn from the mistake? Do you own the mistake, or not?

I’m here in the back of this bus, wondering what our driver — and what the rest of the folks stuck on the Jersey Turnpike — will do next time. Will they change their driving routine? Will they do some research into apps (Google Maps, Waze, etc.) that might be able to offer them a better route? Will they pay more attention to road signs that warn, in giant letters, “SEEK ALT ROUTE”? Or will they blame it on bad luck, on bad drivers, and stick with the habits that got them into this jam in the first place?

Everyone gets the chance to make their own mistakes. But when you make them, accept the blame — and find ways to learn from them.

———

Those are screenshots of one of the routes Google Maps suggested — and the one we took.