A co-worker asked me this week: How busy are you these days?

I’ve been at this job for four months, and my co-worker knows that we have a thousand things to do. We have to improve the way we drive newsletter growth. We have to launch new products. We have to improve our existing products. We have to work more closely with our sales and marketing teams to serve their needs. We have to improve the types of data we collect, and find and build better tools to work with.

That’s why my response seemed to catch my co-worker by surprise: I have a list a mile long of things to do… but I’m not crazy busy.

Yes, there’s a lot to do. And yes, I want to get these things done as quickly as I can.

But I can’t make all these things happen at once. I don’t have the team in place yet to take on all these projects, and I’m still getting buy-in from other teams in the office that we’ll need to work with.

Sure, I could try to run through walls to try to get stuff done. But I know I can’t get past those walls by myself. The only way to get through them is with time, teamwork, and money. But I don’t have those things yet — and if I push too hard, too fast, I’m going to drive myself insane.

Instead, I’m trying to work smarter — not faster. I wrote about this last week in my annual Things I Believe post:

“Direction is more important than speed. It doesn’t matter how fast you’re going if you’re headed the wrong way.”

Building something new is going to take time. For now, the best thing I can do is help point the team in the right direction. I’m spending a lot of time meeting with other stakeholders, figuring out what they want and how it lines up with what I want. I’m spending a lot of time asking questions, and a lot of time listening.

We’re not moving as fast as I want to, but that’s OK. We’re starting to move in the right direction, and it’s OK to take slow steps towards progress. If we’re heading the right way, and if we’re working with the right people and tools, we’ll build up speed over time.

———

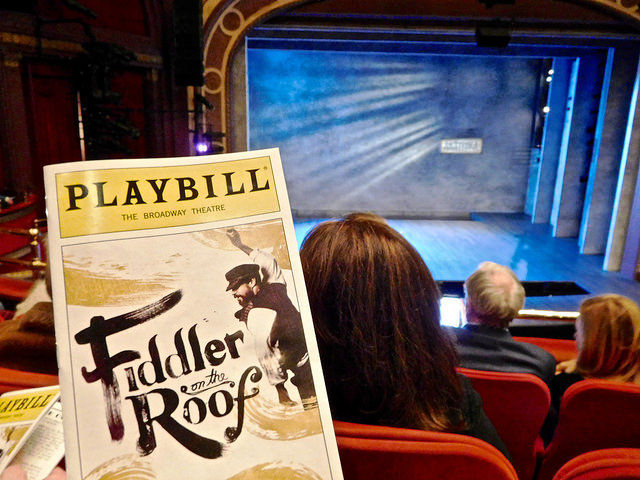

That photo is by Robin Pierre on Unsplash.