So you’ve just graduated — congrats! — and you’re trying to get that first job in journalism. Or you’ve been working in the industry for a while, and you’re hoping to get that next job.

I’ve worked at startups (BuzzFeed), established newsrooms (The New Yorker), and launched two journalism businesses (Stry.us, Inbox Collective). I’ve been lucky enough to hire for my teams, so I’ve got perspective on both sides of the hiring process.

Recently, I got the chance to talk with a class of soon-to-be-grads about how they could think about getting their first job in the field. I shared five key rules for them. I hope these rules will help them — and might help you, too.

1.) Your side project is your ticket in — Launch something! At BuzzFeed, everyone had a side project, and I’ve been a believer in these ever since. It’s never been easier to launch a newsletter, a podcast, a blog, an Instagram, or even a print publication. Show hiring managers what you can do and how you work by launching something of your own.

2.) You don’t need to wait for the traditional gatekeepers. — So many early career journalists only apply to big, established newsrooms. But in some cases, applying to those types of newsrooms might be the wrong approach for you. You might get more experience and more opportunity at a smaller outlet. Project Oasis, for instance, maintains a list of more than 700 local newsrooms, many of which are actively hiring right now. Be willing to start small, and work at a place where you can really grow as a journalist. Don’t worry about the title or the size of the org — find a great team where you can learn a lot and do great work.

3.) Even if they’re not hiring, you can ask if there’s a way to help. — Reach out and see if there’s a way to get involved. Maybe there’s an opportunity to freelance or intern. Maybe they’d be open to bringing you on a role that isn’t listed. Maybe they need additional help on a specific project. Reach out — you never know when you might find an editor or a manager who’s willing to give you a shot.

4.) You’re as good as your ability to stay in touch. — If you do get a chance to chat with someone in a newsroom, even if it’s just for a coffee, follow up and say thank you. Buy stationary and send them an actual thank you note. And stay in touch over the coming years. When you see them publish a great story, shoot them a congratulatory note. So many people never follow up. Don’t be that person!

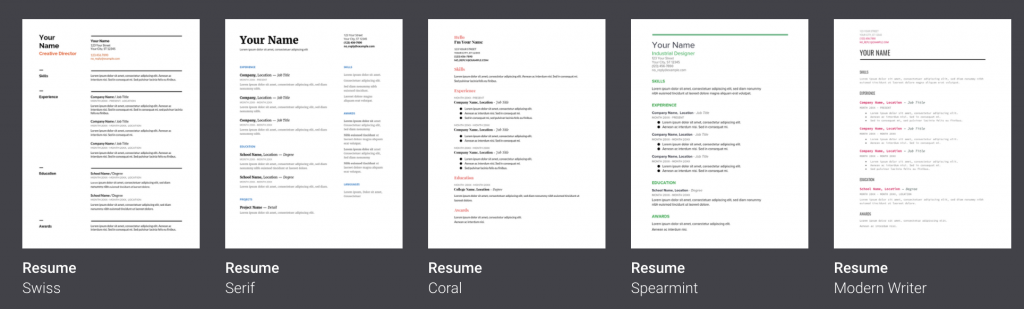

5.) Your next job might be one you create. — There’s never been a better time to create your own newsroom. There are amazing tools — for publishing (CMS), distribution (email, social media, audio), and monetization — to allow you to create a publication. Many of these tools didn’t exist even a few years ago, but they do now. Maybe your first job isn’t at a traditional newsroom — it’s you and a few friends building your own thing. The tools, training — and in many cases, the funding — is there, if you want to start something new.

Remember: We need people like you to tell these stories, and I hope you’ll pursue a career in journalism. Whatever you choose to do next, I wish you good luck.

———

That photo was taken by Hatice Yardım for Unsplash.