A few months ago, I started going to a new gym. I’d been at the same one for a few years, and I generally liked it. It was a huge space, with lots of daily classes, tons of machines, and nice locker rooms. They had multiple locations across the city. But despite that, I’d pretty much stopped going.

It wasn’t the gym itself — it was the location. The gym was a 12-minute walk from my apartment, and on anything less than a perfect day, I’d talk myself out of working out. I’d tell myself that it was too far away to walk in the cold, or too wet, or too humid.

I think I’m like a lot of people: I’ll work out, but only if the gym is so close that I can’t make an excuse for not going. Let’s call that excuse-free zone “the gym radius”: the distance from home or work that a gym needs to be to get you to visit regularly.

My gym radius is tiny: a 5-minute walk from my apartment. When I lived in Columbia and worked out 4-5 times a week, it was because there was a great gym on the ground floor of my building. It’s tough to make an excuse — even in a snow storm — when all you have to do is walk downstairs to work out. In Springfield, the gym was a short drive away — still close enough for me.

Now I’m at a gym that’s a quarter-mile away — five minutes, door to door. It doesn’t have the classes or the amenities of my old gym, but it turns out that I don’t really care about that. All I want are some machines, an area to stretch, and a short walk — that’s enough to get me out a few times a week to do the work.

I’ve been thinking about what this means for the rest of my work. What are the other situations I need to put myself in to do great work? If I were you, I’d be asking:

Do you work well remotely, or do you need to be in an office? — Some people work well in a remote setting, but others feed off of an office environment, where casual conversations might lead to unexpected ideas. (Some of my favorite projects have been the result of a quick chat in an elevator or by the coffee machine.)

Do you work better with others or prefer to fly solo? — Make sure you know the answer here, and find a role that allows you to play to those strengths.

Do you like to operate as a manager or an independent contributor? — Again, understanding your strengths — Do you like to lead? Do you mind taking on responsibility for the work and output of others? Are you willing to make sacrifices for the sake of your team? — can push you towards the right role in a company.

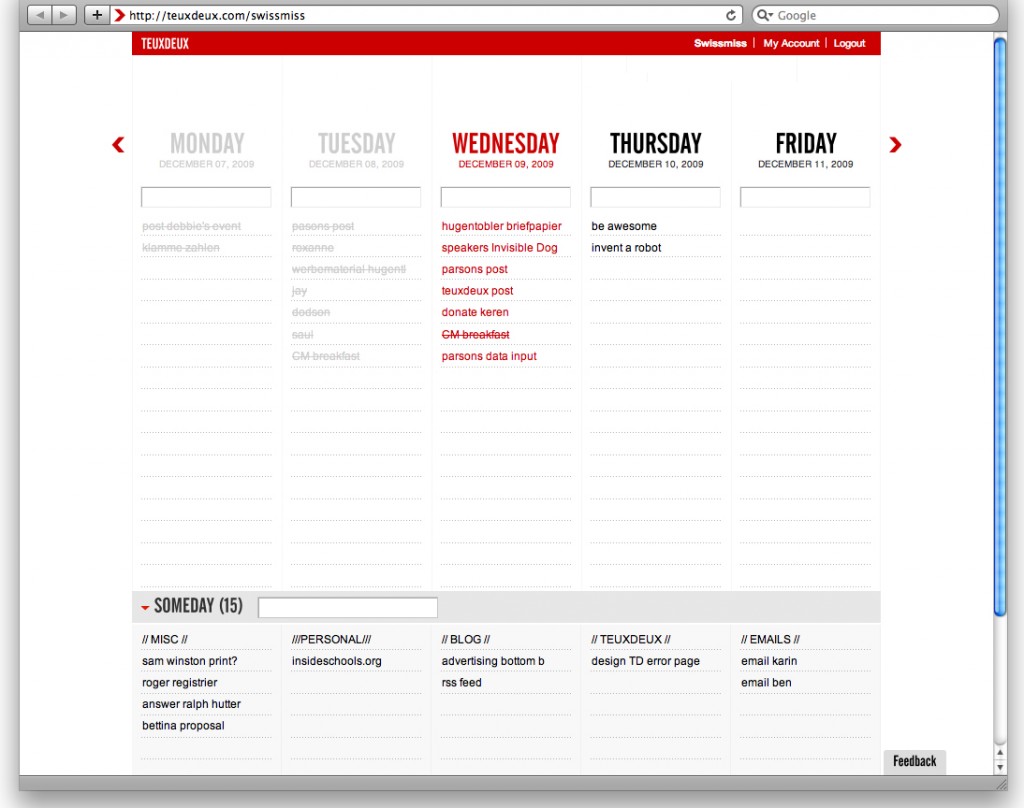

Can you multi-task, or do you prefer to focus on specific tasks? — I’ve found that most people aren’t great multi-taskers — in fact, multi-tasking typically leads to lost of unfocused, unfinished work. If you’re like me — I’m not a very good multi-tasker — then make sure you’re blocking out time during the day to focus in on one specific project. Even a 30-minute window without distractions can be enough to make huge progress on a task.

These questions are just starting places for a bigger conversation about work habits. But remember this: If you want to do your best work, make sure you’re putting yourself in the right situations — and the right settings — to do it.

———

That photo of someone working out comes via Victor Freitas and Unsplash.