I had a Twitter back-and-forth with Therese Schwenkler last week. She’d just written an awesome post about Derek Zoolander and finding yourself.

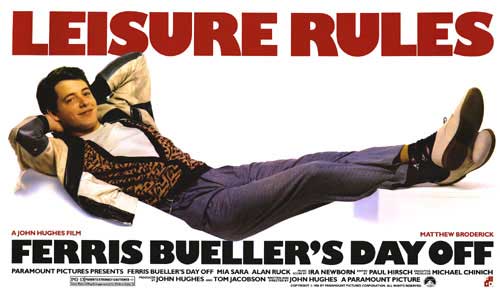

And I joked: “Zoolander” is a classic, but I think my lifestyle (and Stry.us) is more based on “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off .”

.”

Except I wasn’t really kidding.

There’s a whole lot of Ferris in everything I’ve been doing these last two years. The attitude. The rejection of norms. The inability to play by any sort of rules.

Seriously, it’s all there.

But don’t take my word for it. Take Ferris’s:

Ferris: Hey, Cameron. You realize if we played by the rules right now we’d be in gym?

The rules were laid out pretty clearly for me in high school: Get good grades. Get a good SAT score. Go to a good school. Get a good job. Go to a good grad school. Get a better job. Have kids. Coach a soccer team. Send your kids through the same cycle. Retire. Move to Boca.[1. Okay, maybe not the Boca part.]

I can’t remember a single class that taught me that doing what I’m doing now was possible. I was trained to go out and be a part of the existing workplace, to serve my bosses well, and to maybe get the chance to work my way up to boss one day.

This? They mentioned lawyer, doctor and firefighter, but they never mentioned this.

If I played by the rules, I’d be out in the journalism world starting a second or third job as a professional Facebooker by now. Instead, I’m building a start-up.

So I’m not big on rules these days. I think we make our own rules around here.

Cameron: Okay Ferris, can we just let it go, please?

Sloane: Ferris, please. You’ve gone too far. We’re going to get busted.

Ferris: A: You can never go too far. B: If I’m gonna get busted, it is not gonna be by a guy like that.

There have been times when I’ve been told it’s time to give this up. It’s gone on too long. It’s gone too far.

Hell, no.

Every time I get that sense, I push it even a little further. I’m not going to let the doubters keep me from taking Stry.us as far as I can take it.

Our site’s getting old? Let’s build the most beautiful new news website on the planet. Our team’s not big enough? Let’s hire a few guys. Hell, let’s hire five.

Let’s try some live events. Maybe one live events partner’s not enough. Let’s find another.

Let’s tell some stories online. And while we’re at it, let’s syndicate ’em. Online. And in print. And hey, why not?: Let’s do it on the radio, too.

All that’s happening this summer with Stry.us.

Ferris was right: Don’t set limits for yourself. Break beyond them.

Ferris: Look, it’s real simple. Whatever mileage we put on, we’ll take off.

Cameron: How?

Ferris: We’ll drive home backwards.

Yeah, I had a couple of crazy ideas when I started Stry.us. Some worked. Most didn’t.

The crazy ideas keep coming. I’m not sure if any of them will work, but I’m going to push my team to try them anyway. One or two might turn into something big.

Do first, ask for forgiveness later.

Cameron: We’re pinched, for sure.

Ferris: Only the meek get pinched. The bold survive.

One of my earliest Ferris lessons: Get yourself out of a jam once and you’ll know you can do it again.

And again.

And again.

I’m not trying to end up in trouble. I swear I’m not.

It’s just that… trouble sometimes finds me. And when it does, it’s good to know that I’ve always been juuuuuuust smart enough to get myself out of it in the past.

Knowing that I can find an escape again helps in tricky situations.

Ferris: This is my ninth sick day this semester. It’s pretty tough coming up with new illnesses. If I go for ten, I’m probably going to have to barf up a lung, so I better make this one count.

Part of me keeps thinking about the end. About the untimely demise of Stry.us. I have this recurring fear — not a nightmare, just a fear — that somebody’s going to show up one day and tell me, straight up: Dan, it’s been a nice ride. But, uh, we made a mistake. It was supposed to be somebody else on this crazy journey. Turn in your press pass. You’re needed on the fryer at McDonald’s now.

I still might end up on the fryer. But I’m not going to go quietly. I’m going to do like Ryan Adams told me and burn up hard and bright.

Hell, I might end up in a place I didn’t expect/want, but I’m not going to spend my days there wondering what might’ve been if I’d just put in a little more work on Stry.us. I’m not going to leave any “what ifs” on the table. I’m trying everything I can right now.

Ferris: A person should not believe in an -ism, he should believe in himself. I quote John Lennon, “I don’t believe in Beatles, I just believe in me.” Good point there. After all, he was the walrus. I could be the walrus.

The -ism here: All those conventional journalism beliefs I was taught. Time to challenge them all.

And another thing: Be yourself! Not a bad lesson, either.

Ed Rooney: I did not achieve this position in life by having some snot-nosed punk leave my cheese out in the wind.

I like it when traditional news folks tell me that I’m messing with their shit. It means they’re scared of what I’m doing. And if they’re scared, that probably means I’m trying something a little bit risky.

Risky is good. Journalism needs some risk right now. It needs experimentation.

It needs something like Stry.us.

I’m not trying to leave anybody’s cheese out in the wind, but if we do this right, the Stry.us team might build something that saves somebody else’s bacon.

Ferris: Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.

The best Ferris Bueller advice of all.

I’m 24, almost 25. I’m not waiting around for retirement here. I’m young, I’m dumb, I’m hungry. These are amazing years, and I’m trying to build something great with them.

So I tell you now: Be like Ferris. Be a little too bold. Get up and dance a little too hard. Drive a little too fast. Kiss the girl a little too long.

We may not be able to save Ferris, but I want to keep his spirit going.

Bueller? Bueller?

Yeah, he’s still alive here at Stry.us.

It’s an excellent read, but I couldn’t help but laugh at the final chapter. It’s 1997, and Eisner — CEO of Disney — starts predicting the future of his corporation.