A basketball team can put five players on the floor at one time. A baseball team can have 25 players on the roster on game day.

So how do you build the best possible roster with those limitations?

I’ve been fascinated by some of the ways teams are trying to address that question. In basketball, the buzzword of the moment is “positionless.” Instead of trying to find players that fit traditional roles — like a big, burly center to play in the post — teams are looking for players that can fit multiple roles. In today’s NBA, the ideal big man might be asked to dribble the ball up the floor, hit 3s, and also defend inside.

Of course, it’s not easy to find players who can do that. LeBron James is built like a center and passes like a guard — but he’s a once-in-a-generation type player. The challenge is how to find lesser talents that still bring a meaningful combination of skills — scoring, passing, defense — to the table.

Baseball started moving in this direction last season, when the San Diego Padres tried to use their backup catcher, Christian Bethancourt, as an occasional pitcher. (He got hurt in the first month and only played in eight games.) Still, the idea made a lot of sense. On a baseball team, you’ve got eight starting position players and five starting pitchers. That leaves 12 spots for your backups: 7 or 8 pitchers, and 4 or 5 players for the rest of the field. But if you can maximize those spots by having a pitcher who can also field, it opens up new possibilities for a team. Suddenly, you can keep an extra player on your roster — a sixth starting pitcher, an extra pinch hitter — instead.

This year, the Los Angeles Angels have a player on their roster who might really kickstart a trend towards versatility: Shohei Ohtani, a Japanese-born player who came to the majors this year with LeBron-like hype. He’s one of the Angels’ starting pitchers, and when he’s not pitching, he’s the team’s designated hitter. It’s only the second week of the season, but so far, it’s going incredibly well:

Shohei Ohtani is the best story in sports right now. pic.twitter.com/WMtcyMzRJ7

— MLB (@MLB) April 9, 2018

The old model would have forced Ohtani to specialize: You can hit, or you can pitch, but not both. But if Ohtani continues to play at a high level at two positions, this might change the game for good. It could take a few years for the impact to trickle down to college and high school ball, but eventually, you’ll see more players who can serve multiple roles on a team.

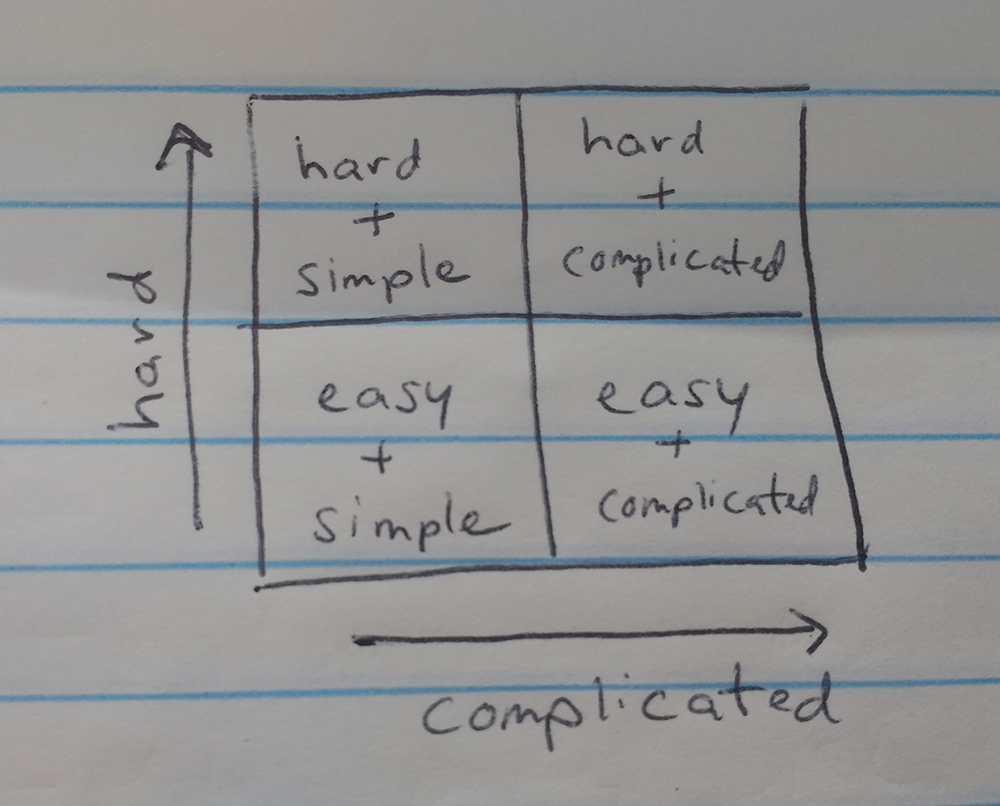

For anyone early in their non-sporting careers, it’s worth thinking about what’s happening here and how it might impact your career. If you had the choice, would you rather pitch yourself as a specialist, or as someone who’s versatile?

There are some limits to versatility: I remember pitching myself after college as a do-it-all backpack journalist, someone who could shoot video, write and report, handle social media, and edit stories. The truth was: I was a hard-working reporter, but barely proficient at the other skills. There’s a big gap between “I can produce video” and “I’m great at producing video.” Companies hire for excellence, not competence.

I wish I’d pitched myself as more of a compromise, a combination of versatility and focus. I was a strong writer, a good reporter, and starting to develop as a photographer. Those three skills made me an interesting candidate. But the more I added in — I talked about work I’d done with interactive graphics in Flash, and experience with data — the more it looked like I was trying to pad the resume.

The point is: Versatility can be an asset. It’s something that might get you in the door at a place that only has so many spots on their team. But if you’re going to pitch yourself that way, you’ve got to be good at everything you do — recruiters will see through it if you’re just adding fluff to your resume.