Last week, I wrote about a big mistake I made when I was first interviewing at BuzzFeed: I didn’t talk to colleagues and mentors about the role, so I incorrectly estimated the value of the job. In the end, I accepted an offer for less money than I should have.

And a few days after writing that post, I realized that I left a key part of the negotiating process out. So let’s discuss it here:

Let’s say you’re about to get the offer. You’ve talked to your network. You’ve figured out what you want to ask for. You’ve done some research online for salary ranges. You’ve asked for your number, and you’ve gotten the offer.

You should go back and ask for a little more.

That HR lead you’re dealing with? They’ve been authorized to give you more money already. It’s probably not a ton of money — depending on the size of the offer, it might be anywhere from 5-10% more. But if you ask for a little more, you’re likely to get it.

How do you actually approach that conversation? You could try an approach like this:

“I’m really excited to work here, and I know that I will bring a lot of value. I appreciate the offer at $58,000, but was really expecting to be in the $65,000 range based on my experience, drive and performance. Can we look at a salary of $65,000 for this position?”

Or:

“I’ve done some research and I see the salary range for comparable positions is $45,000 to $55,000. I think what would be fair for me is $50,000.”

Or:

“I realize you have carefully considered how much you think this job is worth. As we discussed in our interview, I believe I can do this job [more profitably, more efficiently, more quickly, more effectively] by doing [such and such]. For these reasons, I believe my contribution on this job would be worth between $X-$Y in compensation…. Are you open to discussing this?”

Several of my co-workers even referenced Sheryl Sandberg in their negotiations, and got more money.

Yes, it can feel a little awkward asking for more. But they’re almost certainly not going to pull an offer because you asked, and in most cases, they’ve already built in a little wiggle room to offer you more. So go back and ask.

And if they genuinely can’t offer you more: Ask for something else! Ask for more vacation days. If the company offers stock options, ask for more stock. You can even ask to do your next salary review on an advanced timeline. At BuzzFeed, I negotiated my first review 6 months into the job — and ended up getting a five-figure salary bump at that mid-year review.

Ask for a little more. If you don’t, you’re leaving money on the table.

———

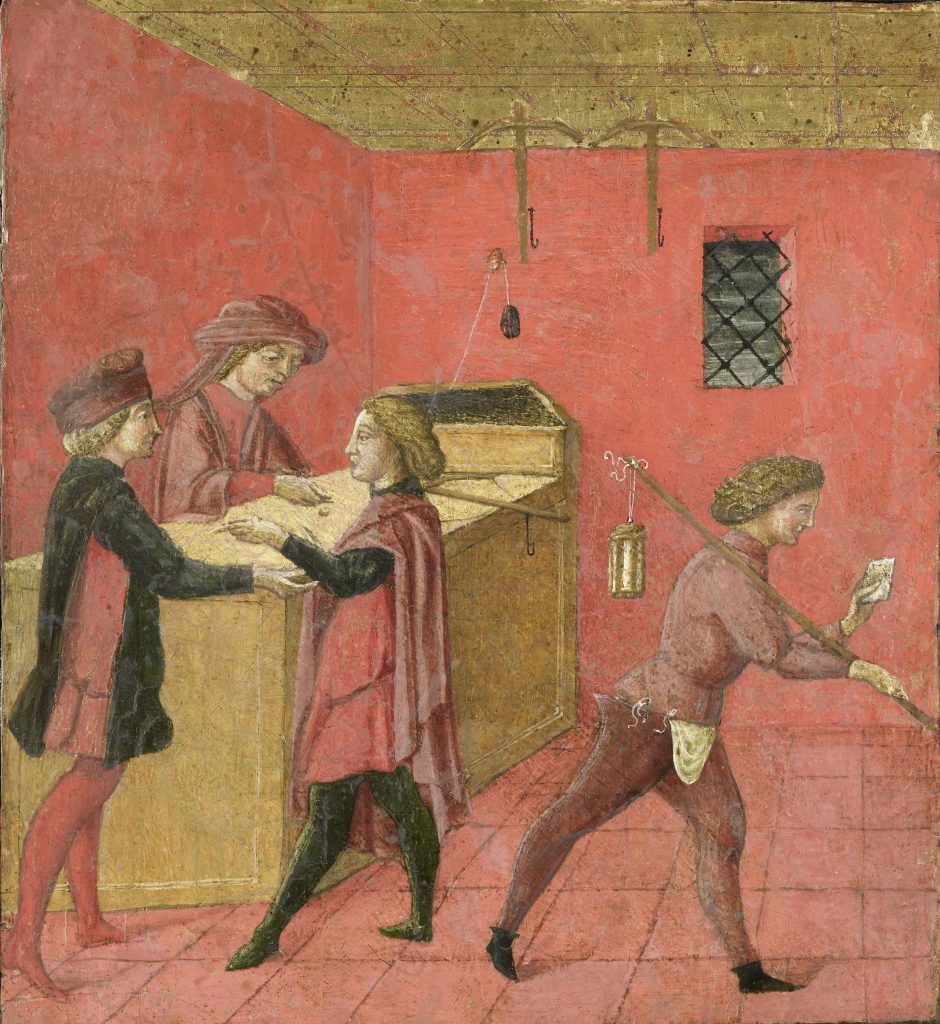

That drawing at top is called the “Payment of Salaries to the Night Watchmen in the Camera del Comune of Siena, anonymous, 1440 – 1460” by anonymous. It’s licensed under CC0 1.0.